We recently had the opportunity to interview Kimberly Blumenthal, MD, MSc, regarding her study Tackling Inpatient Penicillin Allergies: Assessing Tools for Antimicrobial Stewardship, recently published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

What inspired you to conduct this study?

Of hospitalized patients, 15% report an allergy to penicillin, a status associated with increased use of alternative antibiotics that are often less effective, more toxic, more costly, and broader-spectrum. Not administering a beta-lactam to inpatients with infections due to a reported penicillin allergy has been shown to result in three-fold increased treatment failures and adverse events. And evidence indicates that more than 95% of patients with a reported penicillin allergy are not truly allergic. National organizations and both allergy and infectious diseases professional societies have made it clear that addressing this issue is crucial to improving overall care. However, it is currently unknown how best to optimize antibiotic use among hospitalized patients who report a penicillin allergy.

Can you detail the study?

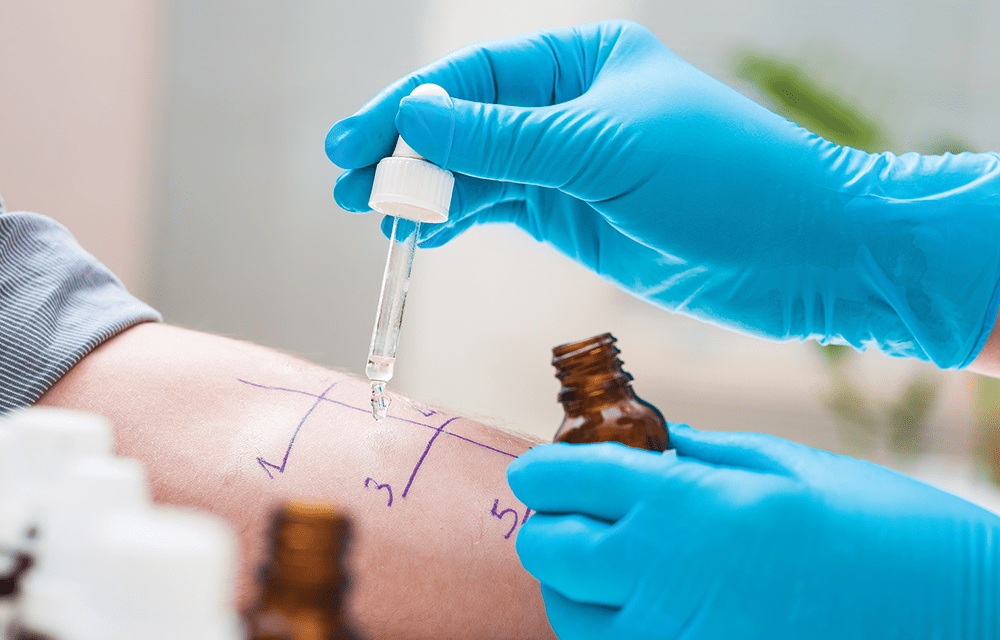

We wanted to determine the optimal method for our healthcare system to address unverified penicillin allergies in inpatients. Therefore, we conducted a prospective study of hospitalized medical inpatients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and compared two interventions to the standard of care (no active intervention). We evaluated outcomes of antibiotic use associated with those two approaches on the inpatient setting: 1) skin testing all possible patients reporting penicillin allergy and 2) using a computerized guideline application (functionally a mobile-friendly website) to help clinicians re-challenge drugs safely and call for a penicillin skin test when needed.

During the first period of the study, we attempted to complete skin testing on as many inpatients on internal medicine with a penicillin allergy prescribed any antibiotic as possible. During a second period, providers could choose to use a computerized guideline application with optional clinical decision support to help them prescribe antibiotics to patients with penicillin allergy. We included all hospitalized medicine patients with a penicillin allergy who received more than 48 hours of antibiotics in the first 7 days of their hospital stay.

What are the most important findings from the study?

We found that the guideline application safely increased the use of penicillins and cephalosporins nearly two-fold compared with the initial standard of care data collection overall. Specifically, the odds ratio when adjusting for patient differences across periods was 1.8. While utilizing skin testing as an inpatient policy did not have a significant impact, patients who were skin tested had a six-fold increased odds of receiving a penicillin or cephalosporin. That discrepancy was due to operational challenges in relying on an inpatient skin testing strategy, which takes time and patient/care team amenability.

We skin tested 43 of skin-test eligible patients, all of whom were found to not be allergic (Figure), which was fantastic, but accomplishing penicillin skin testing of inpatients is challenging operationally. Hiring a designated skin tester would accomplish more testing, but there were other logistic barriers to performing the test—patients were often busy with other procedures or tests, the length of stay (LOS) in the hospital was not very long (7% of patients had LOS <1 day and 16% had LOS <2 days), so coordination prior to discharge was challenging to achieve. Also, only one patient could be tested at a time, for a test that takes about 45 to 60 minutes. Thus, it may not be practical for any hospital to rely solely on skin testing to tackle inpatient penicillin allergies. The guideline approach still uses skin testing when needed, and may be the practical alternative.

Of patients in the standard of care period, 38% were treated with a penicillin or cephalosporin. In the skin-testing period, 42% were treated with a penicillin or cephalosporin antibiotic (not significantly different to the standard of care). In skin-tested patients, 72% were treated with a penicillin or cephalosporin antibiotic, which was significantly greater than in the standard of care. Finally, in the guideline application period, 50% were treated with a penicillin or cephalosporin antibiotic, which also was significantly greater than in standard of care. A greater frequency of skin-tested patients received a penicillin or cephalosporin on discharge compared with standard of care (26% vs 16%) but this was not statistically significant in the unadjusted comparison. Overall frequency of alternative antibiotic use was largely similar across periods.

In the multivariable logistic regression model, we found that patients in the skin-testing period overall did not have a significant increased odds of receiving a penicillin or cephalosporin (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.3). Those who were skin tested, however, had an aOR of 5.6. Guideline/application period patients had an overall increased odds of receiving a penicillin or cephalosporin (aOR of 1.8).

What are the implications of your findings?

The best way to incorporate these findings broadly into practice would be to adopt a common guideline or approach for patients with reported penicillin allergy in the hospital setting. Currently, only about 10% of all hospitals are equipped to perform the penicillin skin test, and most hospitals do not have access to allergists.

While there are operational barriers to addressing penicillin allergy in inpatients, we encourage doing so. Addressing penicillin allergies can take many forms, ranging from allergy history alone, skin testing, and challenge doses to guidelines or applications that incorporate some or all of these methods. It is also important to recognize that it is safe to do skin testing and challenges on inpatients. In this study, only one patient had an adverse drug reaction (pruritus). It requires a practice change in thinking for clinicians and staff to think about giving penicillin and other beta-lactams to this patient population. However, given the breadth of available information, we need to reframe the conversation about penicillin allergy. Not investigating penicillin allergies results in more patient harm than investigating penicillin allergies.

PWeekly

PWeekly