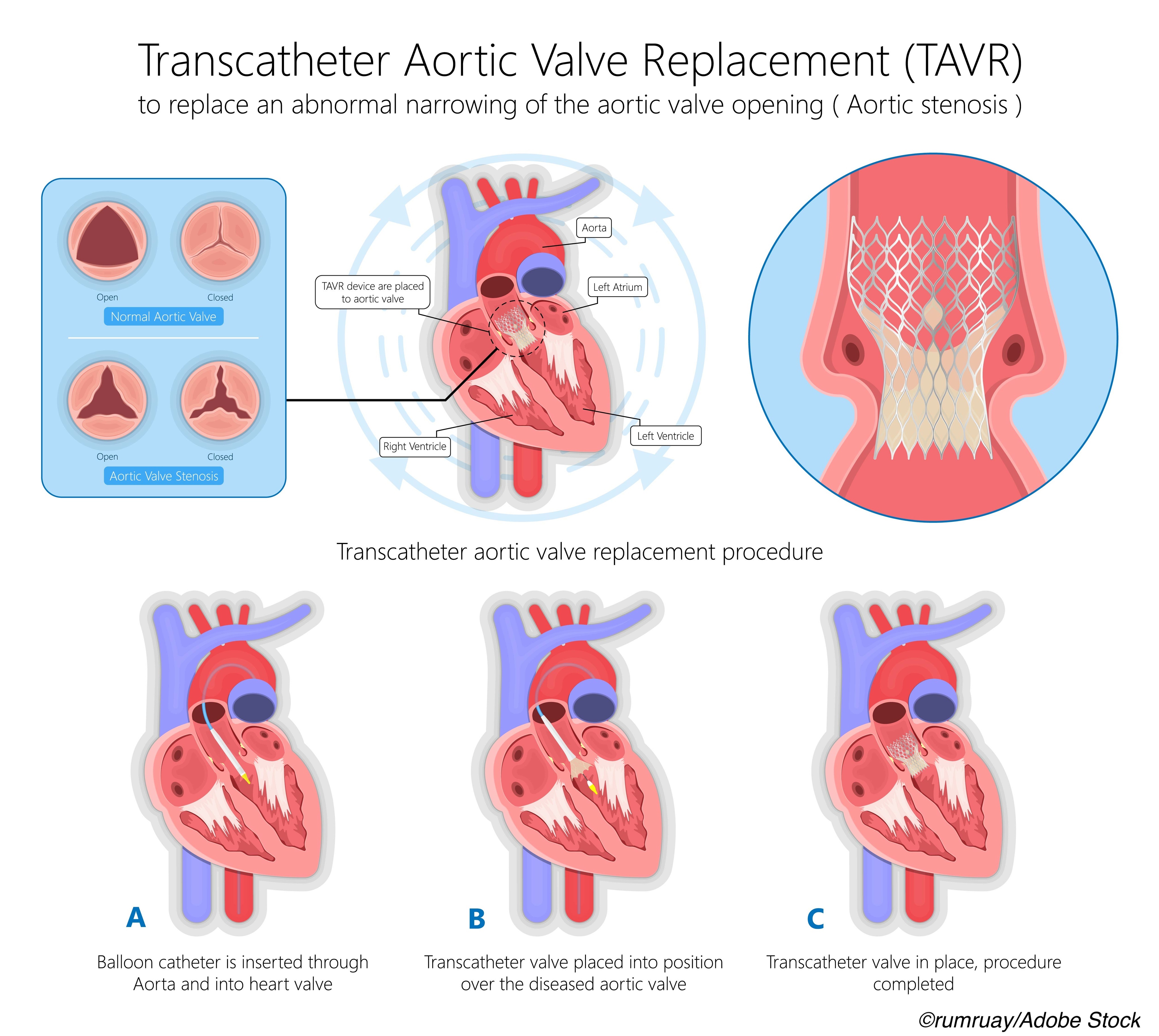

In major metropolitan areas in the U.S. with greater numbers of Black, Hispanic, and socioeconomically disadvantaged residents, rates of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for aortic stenosis were significantly lower, even after adjusting for age and comorbidities, according to a study published in JAMA Cardiology.

“Indeed, the considerable numerical growth in TAVR programs in the U.S. over the previous decade has not been equitable. Hospitals starting TAVR programs cared for patients with greater wealth compared with similar hospitals that did not start TAVR programs. Additionally, communities of lower socioeconomic status had lower TAVR rates than communities of higher socioeconomic status, although questions remain on the prevalence of symptomatic aortic stenosis in different populations. Some of this disparity is explained by geographic factors; most TAVR centers opened in metropolitan areas with existing TAVR centers, and few TAVR centers were initially located in rural areas,” wrote Ashwin S. Nathan, MD, MS, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“However, physical proximity may not be sufficient to guarantee access to a procedure. Biases in initial diagnosis, care delivery, referral patterns, social determinants of health (such as the ability to miss work for medical appointments), availability of transportation to subspecialist appointments and testing, language barriers, lack of trust in the health care system, and other structural factors may also represent barriers to accessing high-technology health care for vulnerable population,” they added.

In an email correspondence, Nathan told BreakingMED: “I am interested in studying and addressing inequities in access to novel cardiovascular technologies and therapies. In a previous study, we identified a geographic inequity in access to TAVR, and in this follow up study, we wanted to see if there were racial, ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in access to TAVR even when people live within the same region as a TAVR center.”

For this multicenter, nationwide, cross-sectional, observational study, Nathan and fellow researchers analyzed Medicare claims data between Jan. 1, 2012, and Dec. 31, 2018, from fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 years or older who resided in the 25 largest metropolitan core-based statistical areas. Their goal was to assess associations between zip code-level racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic composition and TAVR rates.

In all, they included 7,590 individual zip codes within the metropolitan areas, and assigned patients to core-based statistical areas (CBSAs). These CBSAs are “distinct geographic areas consisting of an urban center and surrounding counties that are socioeconomically linked to the urban center by commuting, representing areas where people work and live,” explained researchers.

Mean age of Medicare beneficiaries was 71.4 years, 47.6% were men, 73.8% were White, 11.1% Black, 8.0% Hispanic, and 4.0% Asian.

The median number of TAVR centers per CBSA was seven, and the mean number of TAVRs performed per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries was 249.

Nathan and colleagues found the following:

- For each $1,000 decrease in the median household income, the number of TAVR procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries decreased by 0.2% (95% CI: 0.1%-0.4%; P=0.002).

- For each 1% increase in the proportion of dually eligible for Medicaid patients, the number of TAVR procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries was 2.1% lower (95% CI: 1.3%-2.9%; P˂0.001).

In zip codes with a higher number of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries, TAVR rates were lower despite adjustment for socioeconomic markers, age, and comorbidities. When adjusted for median household income, the following results were seen:

- For each 1% increase in the proportion of Black patients in a zip code, the number of TAVR procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries decreased by 1.1% (95% CI: 0.6%-1.7%; P˂0.001).

- For each 1% increase in the number of Hispanic patients, it decreased by 1.2% (95% CI: 0.2%-2.2%; P=0.03).

Researchers found no significant interaction between median household income and Black or Hispanic background.

“There are significant inequities among racial and ethnic minorities, as well as socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. While they may live within walking or driving distance of TAVR centers, they do not appear to have equal access to the procedure. We need to be proactive as a medical community about ensuring complete access to this life-saving procedure for all people,” concluded Nathan.

What can clinicians do to help balance these inequities?

“We need to engage local communities to ensure that they are receiving good medical care. While we found lower rates of TAVR among racial and ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, this is the final step in a long complex pathway that starts with access to primary care and specialty services,” said Nathan.

Study limitations include a lack of information on why patients did not undergo TAVR including local specialist referral patterns/practices, patient preferences, and patient values; limiting analysis to beneficiaries of fee-for-service care and exclusion of those receiving Medicare Advantage and those who may not have been eligible for Medicare; and possible survivor bias due to differences in life expectancy in different racial/ethnic groups.

In an accompanying editorial, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc, of the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, and deputy editor of JAMA Cardiology, and Ajay Kirtane, MD, SM, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, and associate editor of JAMA Cardiology, highlighted these limitations in interpreting the results from Nathan et al.

“We echo the caution of residual unmeasured confounders; restate concerns regarding the biology of calcific aortic stenosis as a function of genetic ancestry; and add survival bias given the shorter life expectancy as a function of race,” they wrote. “As the current analyses portray, disentangling race from the entirety of the social construct is a complex and uncertain exercise. Is it possible that there are race-based biases impacting TAVR at the patient level? Yes. Is it proven? No. Equity in access to care and completeness of clinical assessment, including even a careful physical examination, also come into play when assessing disparities in a ’downstream’ procedure such as TAVR.”

Ultimately, Yancy and Kirtane concluded, race is not the only explanation for these disparities in care.

“Where does the truth reside? As the authors imply, access to and referral for high technology procedures predicated on team-based decision making are subject to bias. But, race per se is not the sole culprit explanation. Until more research and research methodology evolve, we must do more to recognize our possible biases and concomitantly exercise caution before concluding race-based disparities in the utilization of TAVR. We can be empathic but we must also be sure,” they wrote.

-

In the United States, zip codes with higher proportions of socioeconomically disadvantaged, Black, and Hispanic populations had lower rates of TAVR compared with zip codes with more affluent and White populations.

-

For each 1% increase in the number of Black and Hispanic patients in a specific zip code, researchers found decreases of 1.1% and 1.2%, respectively, in TAVR procedures per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries.

Liz Meszaros, Deputy Managing Editor, BreakingMED™

Nathan reported no disclosures.

Yancy reported spousal salary support from Abbott.

Kirtane reported institutional funding to Columbia University and/or Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, and Neurotronic, consulting fees from IMDS and travel expenses/meals from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, Siemens, Philips, ReCor Medical, Chiesi, OpSens, Zoll, and Regeneron.

Cat ID: 308

Topic ID: 74,308,282,585,399,730,308,914,255,925,159