By Takashi Umekawa

TOKYO (Reuters) – Japanese doctor Yasushi Goto remembers prescribing the cancer drug Opdivo to an octogenarian and wondering whether taxpayers might object to helping fund treatment, which at the time cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, for patients in their twilight years.

Japanese have easy access to new medicines, whose prices are decided by the government and subsidized by the country’s public health insurance system.

But that may change. Japan, confronted with the ballooning cost of caring for an aging population, is introducing a cost-effectiveness test for drugs as a means of capping prices.

There are no plans to deny care for patients of any age. But limiting the prices of innovative but costly treatments might chase new drugs out of the $86 billion Japanese market, drugmakers say.

“If you ask whether it’s worth prescribing an 85-year-old patient Opdivo, a lot of people will say no. But patients and family members are going to say yes,” said Goto, who works at the National Cancer Centre Hospital.

Patients also fear more drastic changes, such as denying access to new medicines; Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s economic council in December proposed considering cost in determining whether to approve treatments.

“For cancer patients like us, it’s not acceptable if the government applies a cost-effective analysis in determining whether to approve treatments,” said Yoshiyuki Majima, a director of patient advocacy group Rare Cancers Japan.

SUSTAINABILITY OR ACCESS

The Japanese government estimates that public medical spending could surge 75 percent to 68.5 trillion yen ($624 billion) by 2040.

“It is obvious that Japan will face difficulties in providing social security service,” said a government official involved in the discussions, declining to be named because he is not authorized to speak to media. “The cost-effectiveness analysis is a means to secure sustainability.”

The system that will be adopted in April, according to a draft published on the health ministry’s website, compares the cost to the effectiveness of new treatments using an “incremental cost-effectiveness ratio,” or ICER.

ICER, already used in countries such as Britain, considers how much it costs to give a patient one additional year of healthy life compared with existing alternatives. If that exceeds 5 million yen, for example, the government may insist on a lower price, according the policy draft.

There has been little public discussion; weekly meetings so far have involved mostly Health Ministry officials, doctors, academics and drugmaker executives.

“If I have rheumatoid arthritis and I can’t write or type, but then I get a treatment that enables me to go back to work, pay taxes, and take care of my family, that benefit is not going to be captured by the ICER,” said Kevin Haninger, a vice president of Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, a lobbying group.

In an interview with Reuters, he insisted Japan should carefully consider an impact on the industry when introducing such analysis to reduce drug prices.

“If Japan is going to cut prices so much, I think Japan will really run a risk of losing its current position,” he said.

LUCRATIVE MARKET NO MORE?

Drugmakers have been complaining about price cuts since 2017, when the government decided to review costs more frequently.

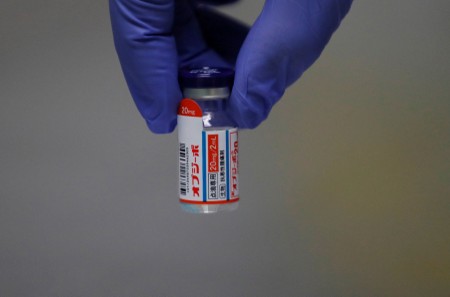

Japan has slashed the price of Opdivo, developed by Ono Pharmaceutical Co Ltd and Bristol-Myers Squibb, by more than 75 percent in the last two years. It has also lowered Gilead Science’s hepatitis C drug Sovaldi by 32 percent since 2016.

But while drugmakers threaten to pull back from Japan, the government is prepared to call the industry’s bluff, saying Japan is too lucrative a market for companies to ignore, according to two government officials, who declined to be named because they are not authorized to speak to the media.

Unlike the United States, where insurers may deny claims, or the UK, where patients can be denied costly drugs, Japan is seen as a relatively predictable market because of its social insurance system.

For example, Novartis’ Kymriah, a type of therapy in which a patient’s T-cells are modified to attack cancer cells, is expected to be approved in Japan this year.

The price for pediatric leukemia patients, to be set by a government panel after approval, is expected to start at about $475,000, similar to U.S. prices. With an estimated 250 Japanese eligible for treatment with Kymriah, sales in Japan are a potentially lucrative addition to Novartis’ bottom line.

Novartis declined to comment on potential effects of a new pricing policy.

Goto said the government should focus on reducing prescriptions for illnesses that are not serious, rather than costly but possibly life-saving treatments for a small number of patients.

“Flu medicines, for example, can be seen to have very low cost-effectiveness because they don’t save people’s lives, except those of infants or pregnant women, compared with cancer drugs that are critical for some patients,” he said.

(Reporting by Takashi Umekawa; Editing by Ritsuko Ando and Gerry Doyle)