Many products used in the clinical environment have undesirable features, packaging, or presentation and may result in wasted effort as well as risk to clinicians and patients. However, when physicians provide feedback and influence purchasing decisions, it often has little effect on what is ordered and put into service. We explore why physicians appear to be a weak constituency in nearly all health systems and what can be done to fix this unhealthy situation.

Products being used in the care environment are often ineffective or create unnecessary burdens on clinicians, but the processes for using clinician feedback to develop more suitable requirements or to improve purchasing decisions are frequently unclear and sub-optimal.

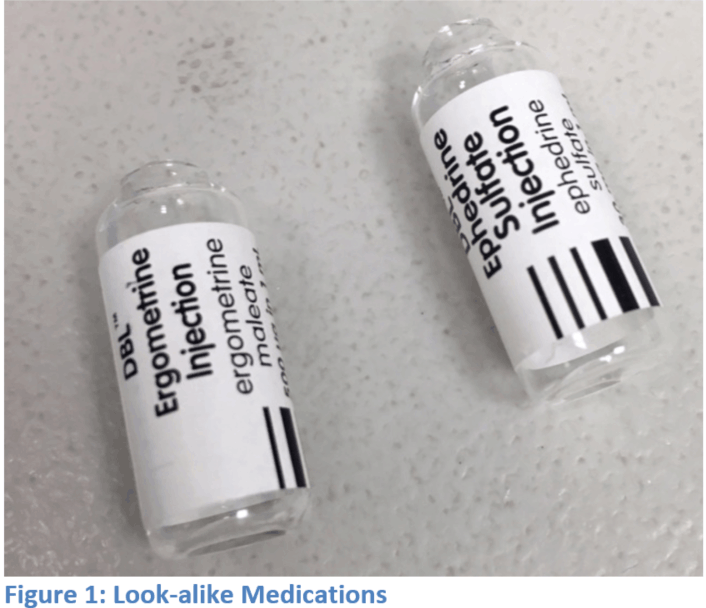

Even when clinicians find fault with a product, this is seldom considered for any future procurement requirements and purchases. For example, the Clausen Hook on anesthesia masks is often removed and discarded by clinicians at point of use, adding to waste and creating unnecessary tasks. Ineffective or undesirable products may also carry significant risks, such as look-alike/sound-alike medications as those seen in Figure 1 (kindly provided by PSNetwork.org)—so much so, that several fatal accidents have stimulated a Change-org petition against indistinct chlorhexidine. Clinician requests to have clear, unique, and standardized medication labels seem to fall on deaf ears.

An informal poll of physicians suggested that they viewed themselves as a weak constituency in nearly all health systems, and that general feedback by physicians with regard to equipment, materials, and other products is rarely considered by administration.

Looking at potential exemplars of processes in which physician input is sought and used for acquisition of products, one might think that the “Doctor Preference Card” (DPC) might work well. The DPC is used by surgeons to indicate product and environmental needs specific to a case or type of case. This may include the types of surgical tools, even to the degree of brand and model, larger equipment such as cautery machines, surgical robots, etc., or aspects of the surgery itself relating to space, lighting, etc. The DPC gives the surgeon a degree of control over exactly what products are available in the surgery, and thus a means to influence all aspects of the acquisition process—from requirements, to purchasing, to inventory.

However, Dr. Renate Ilse (@IlseZorn) points out that there are some potential drawbacks with using the DPC as a model for physician input: when a large proportion of surgeons desire different rather than standardized equipment, the logistics and expense can become prohibitive. As a result, those in charge of purchasing may begin to resist these requests, and DPC requests could cease to be a viable means to gain input on product fit. In her experience, the DPC process is often kept completely separate from routine acquisition processes, and in many facilities, there has never been any link between DPCs and hospital procurement processes, except in rare occasions in which a surgeon has an approved exemption from a standardized product. In such cases, the product may be purchased separately using an ad hoc process, rather than being part of a regular process.

That brings us back to the simple thought that physicians lack a robust and rapid process for factoring clinician feedback on products into the acquisition process in order to improve purchasing decisions—the objective being to reduce wasted effort, potential confusion, cost, and clinician or patient risk.

Why Don’t Physicians Speak Up? Why Are They Not Heard?

In one case, a hospital tried to switch to cheaper intravenous (IV) products and supplies, and the nurses collectively rebelled and entered so many safety reports and complaints that the hospital switched back to the previous orders.

The facility had not consulted front-line clinicians for input before making the switch, and not even the IV team were asked for their opinion prior to the fact. As a result, there were serious safety and patient care issues, because the new catheters weren’t stiff enough and caused more blown sites and potential needle-sticks. In addition, the insertion wasn’t a closed system, and this resulted in frequent blood spillage.

Some physician’s report that their facility purchasing department is often resistant to clinician input and tends to find excuses for not doing anything. Contracts take a long time to negotiate, and administration staff are often hesitant to make changes. This may be especially true in hospitals that have contracted with buying groups to do their procurement. To accommodate clinician feedback, a program director has to demand action, provide evidence, and sometimes “kick it up the chain,” and—where there is a patient safety issue—organize a meeting with the vendor.

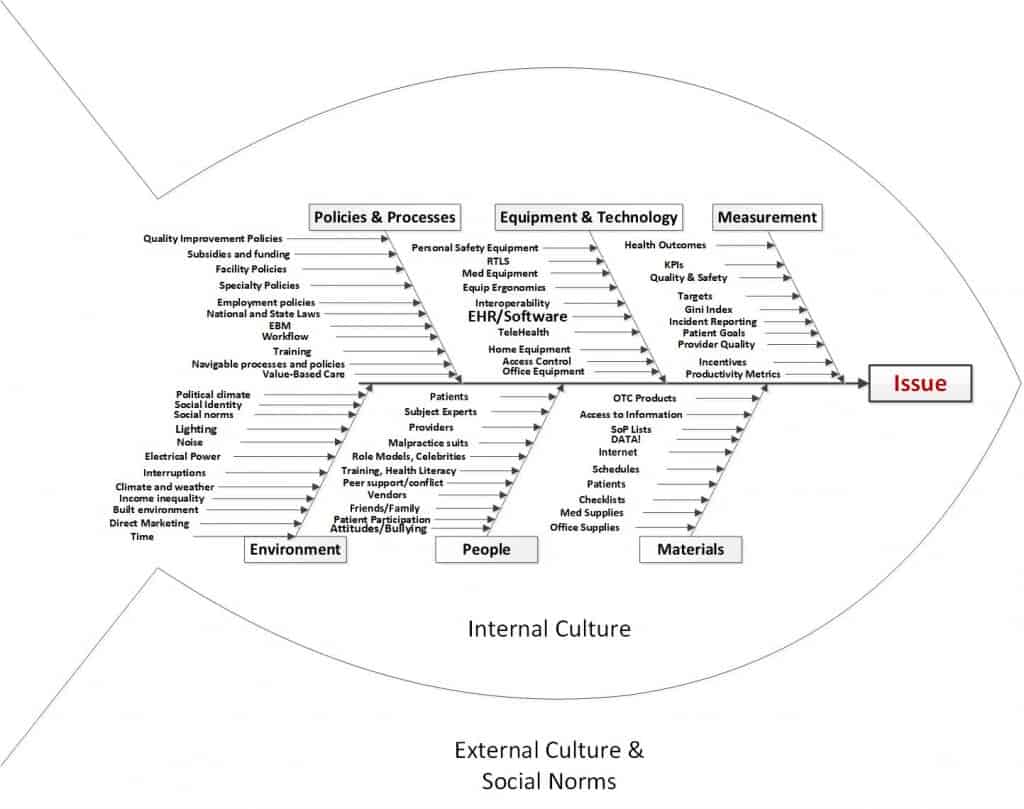

Let’s explore the dimensions of the standard process improvement Ishikawa diagram (Figure 2) and cover each of the fishbone topic areas to cast light on why physicians are a weak constituency with regard to setting of requirements for the purchase of products.

Figure 2 Cause and Effect Diagram

- Policies & Processes

There is seldom a documented and well-rehearsed process for physicians to influence the acquisition process, and few opportunities to communicate on-the-ground feedback on product performance. DPC is not a viable exemplar, and using the safety reports should be a last resort in cases of injury or patient safety risk.

An open question is why physicians don’t get included in the setting of purchasing policies as a matter of process. Are physicians asked for input for acquisition requirements as part of a documented process, or are they perhaps systematically excluded from these processes? Given their deep understanding of the delivery of care, shouldn’t there be mandatory approval by a physician who uses the equipment or supply? - Equipment & Technology

Do physicians have access to the programs or systems in which requirements are set and purchases made? Frequently, the enterprise resource planning systems (eg, SAP) are not available to clinicians, and they have no ability to enter information or provide ratings in those systems. - Measurement

In many cases, products are indeed ranked according to performance and cost of ownership, but these may be entered solely by administration staff without any feedback from clinicians (even informally). Purchasing cost may also be weighted and count more than performance measurements.

Several questions could be asked of the process owners:- Is physician satisfaction or rating of product quality part of the purchasing process? Just as consumer reports poll consumers about the products they use, shouldn’t physicians and nurses be polled to determine the products they find most effective and most valuable?

- Do low-rated products get subjected to a review or a ban?

- Do highly rated products get promoted in the purchasing process?

- Environment

The meetings, discussions, and decisions may be made in administration blocks or offices physically distant from where the clinicians work. As a result, clinicians may not be present and may not even have security access to them.- Are these purchasing decisions made in places or at times that exclude physicians?

- Are physicians siloed out of product and purchasing discussions?

- With the availability of video conferences, physical distances can now be overcome and physician input can now be conveniently included in these important discussions.

- People

Clinicians may not even know who makes these decisions or how to contact them, and organizational silos may make both the clinicians and administrative staff involved feel that they “aren’t allowed” to talk to each other.- Do clinicians know to whom they can send broken or defective examples for examination?

- Are there power struggles with particular people over purchasing decisions?

- Materials

Some facilities run pilots and provide samples to clinicians prior to making purchasing decisions, but this is not universal.- Do clinicians get sample products to examine or try before purchasing?

- Is there a mature piloting process in which clinicians can test out prospective products as part of evaluation?

The divide between those providing the clinical care and the administrators who order the equipment needs to be closed. Administrators are usually systems experts, and clinicians are experts in the details of delivering quality patient care. The two must work hand in hand for an optimal process to exist.

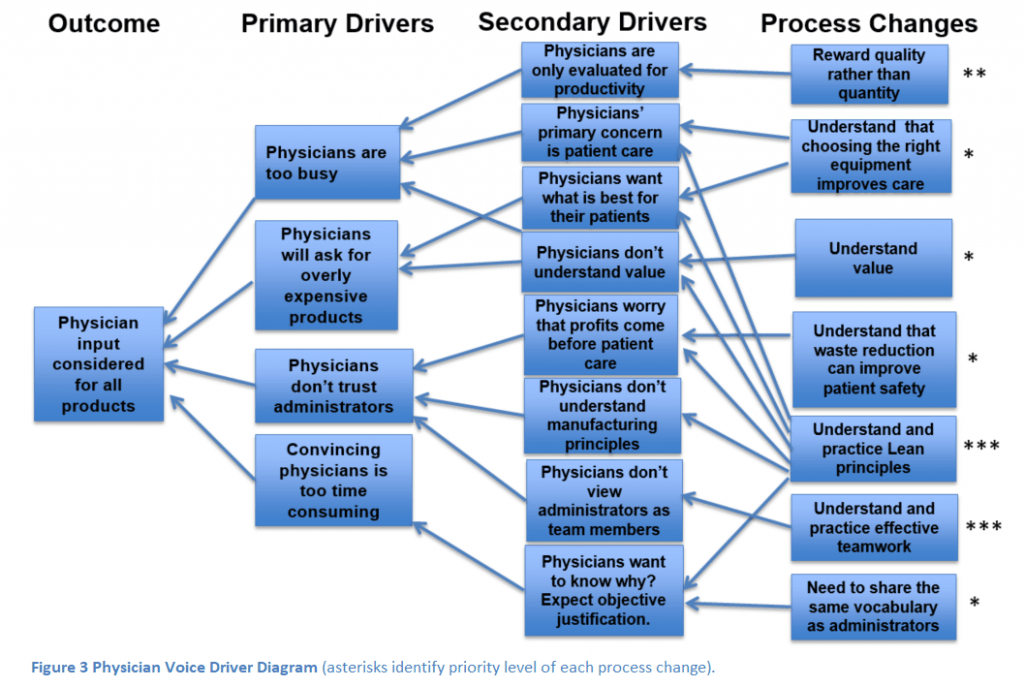

In the driver diagram (Figure 3), we plot out the factors that influence the desired outcome of physicians having a say in the products used in their clinical environment.

The key factors in having physician voice integrated in purchasing decisions are trust, relationships, and time. If we reward physicians for quality rather than the quantity of care, physicians can devote more time to improving the systems of care in which they work.

Devoting more time to improving systems will involve working more closely with administrators to achieve common goals and result in improved trust.

However, in order to work effectively with administrators, both groups will need to deeply understand Lean principles and be able to work effectively in teams. To reach this state, physicians need knowledge of Lean manufacturing principles, and both physicians and administrators may need some brush-up on teamwork training.

Conclusion

Physicians need to identify when their efforts will be of high value. Providing input about new equipment that affects how they care for patients is a very high-value activity and should be identified as a priority.

The description of the hospital administrators that ordered sub-standard IV catheters is an example of how this principle was not followed. Fortunately, the nurses and physicians all united in opposition, but this decision should never have been made without input from the frontlines in the first place!

If we are to become highly reliable organizations, we need to identify where the true expertise lies when it comes to ordering products that affect care quality and tap that expertise as part of repeatable processes. We need to free up physician time, focus efforts on quality over quantity, and drive toward physicians and administrators having a shared focus for quality of care and continuous improvement.

To reach the optimal state, physicians and administrators will require a deep understanding of each person’s roles and appreciation of their expertise. It will also require that we develop a new level of trust that we will all do what is best for our patients.

PWeekly

PWeekly