Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth most prevalent cause of cancer-related death worldwide, and incidence in the US has tripled in the last 4 decades. Excessive alcohol consumption is one the leading pathways to HCC in both the US and worldwide, and it comes with severe prevention and treatment barriers due to social customs, dependence, and stigma. We describe the alcohol pathway to HCC in this post, as well as the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options for this pathway.

In a previous post on HCC care considerations, we described four leading risk factors and causal pathways for the development of HCC. Here, we provide some tools and resources to help identify HCC, ways to link patients to suitable specialists, and guidance finding appropriate studies and trials for your patients.

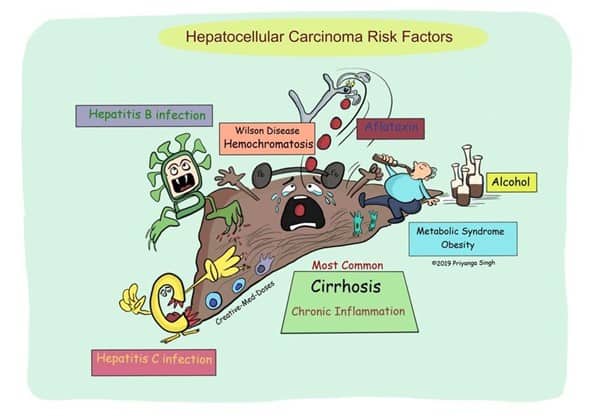

Figure 1. HCC Pathways (c) @Creativemeddose

Figure 1. HCC Pathways (c) @Creativemeddose

Of the several causes of HCC shown in Figure 1, we focus on the four leading HCC risk factors in this post, a previous post covering the viral pathways, and a future post to cover Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) leading to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH):

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- NAFLD leading to NASH

In this post, we will focus on alcohol consumption as a pathway to HCC.

Alcohol & the Social Environment

A major hurdle to any discussion of the role that alcohol plays in the development of liver damage is that the topic faces immense social barriers resulting from stigma and denial. On the one side is denial by patients or their caregivers that the amount or rate of alcohol use is putting them on a path to harm. On the other side, stigma exhibited by the public at large, many political leaders, and even some clinicians results in an environment in which frank and open discussion is made difficult or even impossible.

An overarching social environment often exists in which alcohol consumption is present or even core to many social expressions. We speak of “toasting” something, “raising a glass,” or saying we will “drink to that,” and social events and functions often revolve around drinking alcohol. Some families or communities regard alcohol consumption as a rite of passage and the ability of someone to “hold their liquor” regarded with a sense of pride.

Individuals also vary greatly in the amount of alcohol that lies on the risk threshold, making it difficult to clearly delineate boundaries between safe and unsafe consumption. However, the CDC provides a general guideline that sets an upper limit, past which the risk of harm climbs sharply. They advise people to “drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men or 1 drink or less in a day for women, on days when alcohol is consumed.” The total blood alcohol level is also important, and the CDC recommends that blood alcohol concentration (BAC) should remain below 0.08 g/dl. A BAC of 0.08g/dL equates roughly to 5 or more drinks by a man of average build or 4 or more drinks by a woman of average build in a 2-hour timeframe (binge drinking). It bears emphasizing that the CDC recommendations specify the harm boundary and that they are not suggesting that these consumption rates should be treated as the norm.

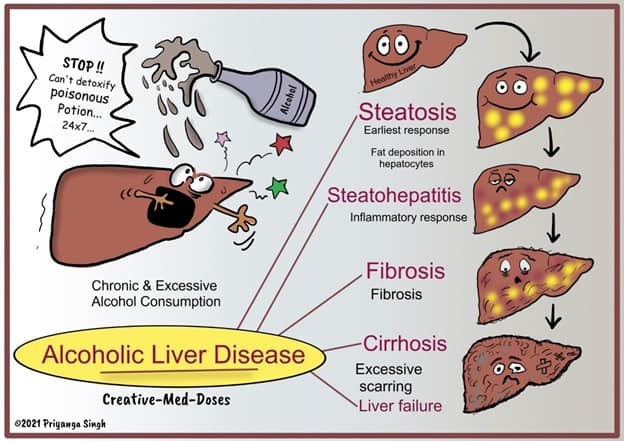

Liver damage can be classified into four sequential stages (Sakhuja, 2014) :

- Steatosis

Fatty liver (steatosis) is the first and most common liver response to chronic alcohol consumption and binge drinking. Steatosis was historically considered a relatively harmless side effect of heavy alcohol use, but evidence has accumulated that suggests that this stage is neither benign nor safe to ignore. Fat deposition is a sign of incipient damage, and steatosis is already firmly on the path to HCC. - Steatohepatitis

At this stage, there is evidence of early but detectable liver damage that takes the form of hepatocyte ballooning, inflammation in the lobular parenchyma, and apoptosis. HCC risk is present in this stage. - Fibrosis

Often starting with zone 3 of the liver, damage extends in a pericellular or perisinusoidal pattern (sometimes said to be a “chicken wire” pattern). At this point, there is damage that is probably manifesting in ways that are observable to the patient, and the risk of HCC is elevated. - Cirrhosis

The cirrhotic liver is the final stage of damage, with often profound loss of capability and capacity, as well as overt and unmistakable health effects, including the potential for complete liver failure. Some 5%-15% of patients with cirrhosis develop HCC.

Figure 2. ETOH HCC Pathway (c) @Creativemeddose

The likelihood of Encountering Excessive Alcohol Use in Your Patients

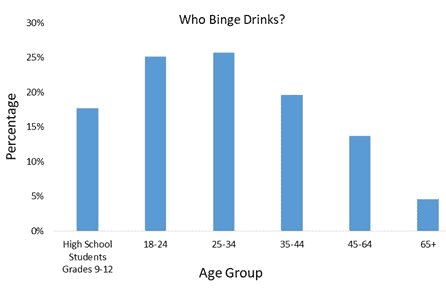

The average American adult consumes an equivalent of 9.8 L of pure ethyl alcohol per year, or approximately 700 standard drinks. In other words, about 1.9 drinks per day, and therefore 96% of the CDC recommended daily limit. Even more worrisome, CDC binge-drinking data suggest that one in six US adults binge drink and do so approximately 4 times per month. On average, they consume seven drinks per occasion. With an average patient panel size of 2,300, most primary care physicians will likely have more than 380 patients who meet the definition of binge drinking, and far more will be drinking more than the recommended daily limit. Figure 3 shows the CDC drinking distribution by age.

Figure 3. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2015.

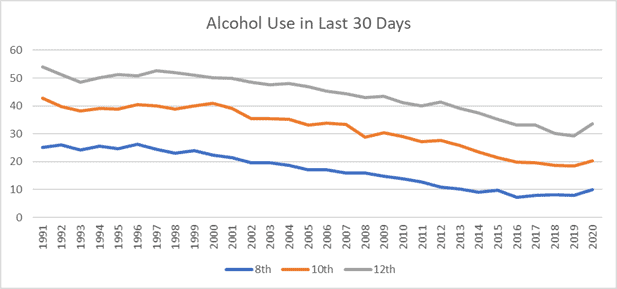

The reported incidence of alcohol use in children remains high and is of concern. Primary care physicians should remain vigilant of underage drinking. The “Monitoring the Future” data from cross-sectional in-school surveys are available from the National Addiction & HIV Data Archive Program (NAHDAP), a part of the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). Figure 4 shows trends in underage drinking derived from these data.

Figure 4. Percentage Use of Alcohol Past 30 days (Source: Monitoring The Future)

How to Discuss Alcohol Use With Patients

Many risk-reduction materials and methods are available to the primary care clinician that may be of great help in screening for excessive alcohol use, intervening in an evidence-based manner, and developing care plans that have a lasting effect. The Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention approach has been developed over the last 30 years and has proven to be effective. Several other institutions offer specific or tailored materials, including practice guides, implementation guides, and discussion guides. For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) offers an alcohol use practice manual that includes a screening and brief intervention program. Similarly, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) offers discussion guides like “Talking with Your Adult Patients about Alcohol, Drug, and/or Mental Health Problems.

How to Discuss Staging With Patients

Discussing HCC staging with patients can be difficult. The public literature available to patients often contains misleading information, while the most trustworthy and authoritative information is usually aimed at clinicians and often only available behind paywalls. Blue Faery provides clinically accurate materials that patients will find understandable. These materials are designed to assist physicians in describing the staging and to help patients understand where they are in the spectrum.

These materials include:

- HCC patient education brochures, written in layman’s terms and intended for patients to read.

- The Blue Faery HCC staging discussion pad, which contains anatomical graphics and easily understood text. Each double-sided sheet has space for clinicians to add notes for their patients to use after an appointment.

- The Patient Resource Guide for Liver Cancer, a 20-page booklet with explanations and resources pertinent to patients with HCC and their caregivers.

Blue Faery will send these free materials to any requesting physician.

How to Find HCC Specialists, Treatment Options, & Clinical Trials

The treatment of HCC is best approached with a multidisciplinary team coordinated by a primary care physician. The most effective approach will likely require the expertise of multiple medical professionals and may include an oncologist with experience in HCC, a gastroenterologist, a hepatologist, an interventional radiologist, a radiation oncologist, a surgical oncologist, and a transplant surgeon. To find all clinical trials, the best option is clinicaltrials.gov, but this website can be confusing and difficult to navigate. To assist clinicians in guiding patients to relevant trials, Blue Faery provides a custom HCC clinical trial navigator.

Community Support for Patients With HCC

Patient communities help provide patients with practical tips for their care journey and are often a source of emotional support by people who understand the experience. The Blue Faery Liver Cancer Community is a free, HIPAA-compliant, online community where patients and caregivers are welcome to join and to seek or exchange information relevant to HCC care. Members ask questions, discuss concerns, and find common ground as they navigate their cancer journeys. The forum moderators include community ambassadors who were former caregivers of patients with HCC.

For one-on-one patient support, Blue Faery has partnered with Imerman Angels, a nonprofit organization that provides peer-to-peer support services for the liver cancer community. Blue Faery and Imerman Angels believe that no one should face cancer alone.

A Pressing Need

There is a pressing need to reduce the alcohol pathway to HCC, and primary care physicians have materials at their disposal that can help to interrupt that pathway. To further aid in the care of those who have developed HCC, Blue Faery provides free, patient-readable, and clinically accurate materials to assist clinicians in discussing their patients’ staging, options, and resources.

PWeekly

PWeekly