Performance on smell identification tests was associated with olfactory bulb volume (OBV), research from Germany showed.

“The findings of this cross-sectional study indicate that OBV is independently associated with better odor identification function in the general population and is a robust mediator of the age-dependent association between volumes of central olfactory structures and olfactory function,” reported Monique M.B. Breteler, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Bonn, and colleagues in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

“Given that olfactory dysfunction is a common and early feature of many neurodegenerative diseases, OBV may serve as a preclinical marker for the identification of individuals who are at an increased risk for developing neurodegenerative conditions later in life,” they wrote.

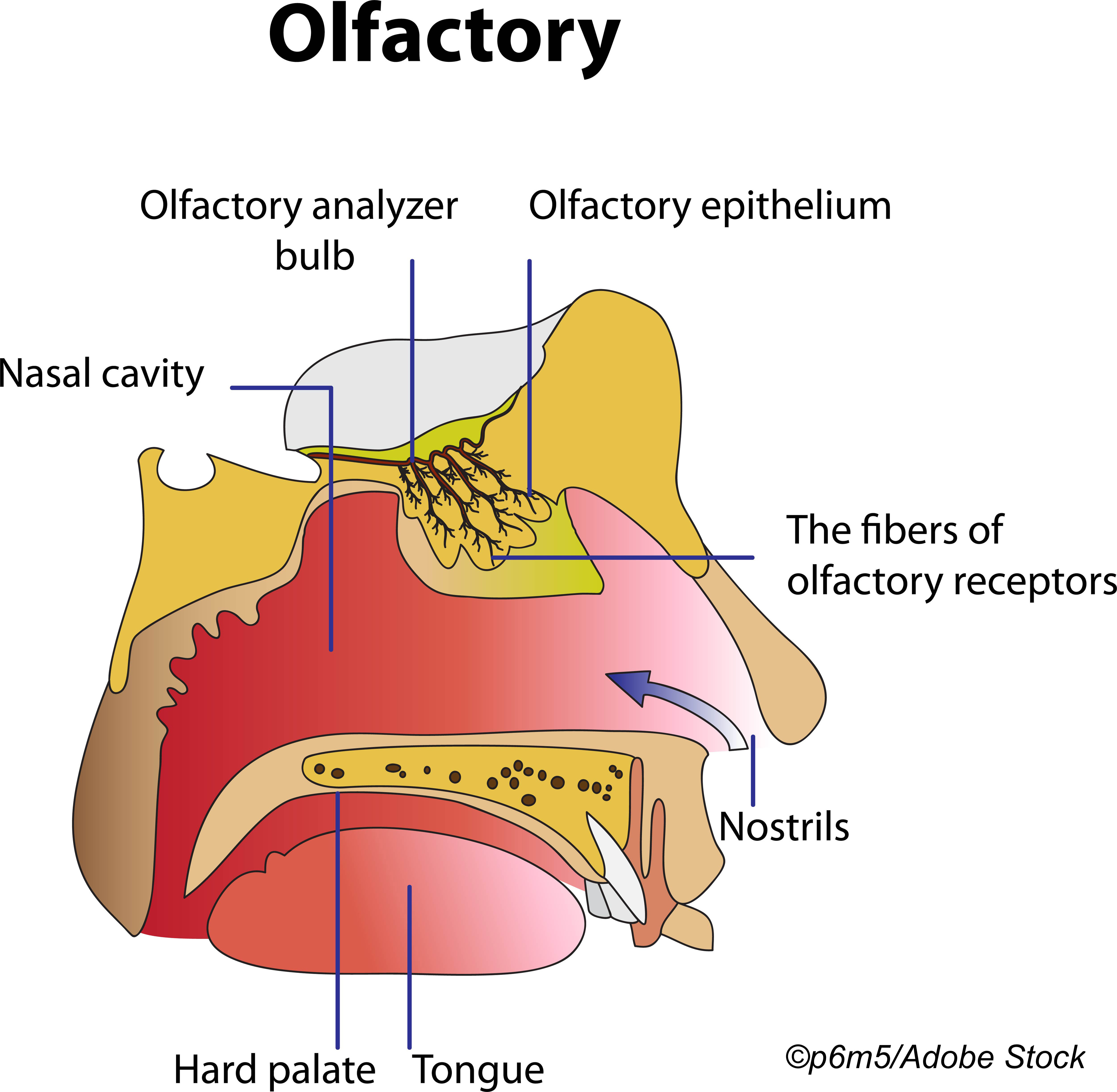

Investigators analyzed data from the Rhineland Study, an ongoing prospective cohort study of neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in Bonn. They included 541 adult participants 30 or older enrolled between March 2016 and October 2017 with olfactory test data and 3-Tesla MRI of multiple areas involved with olfactory processing (olfactory bulbs, entorhinal cortex, amygdala, parahippocampal cortex, hippocampus, insular cortex, and lateral and medial orbitofrontal cortex). The mean age of the cohort was 53.6 and about 57% were women.

Larger OBV was associated with better olfactory measured with the 12-item smell identification test (SIT-12), with a difference in SIT-12 score of 0.46 points (95% CI 0.29-0.64). Participants correctly identifying 9 or less of 12 odors were considered hyposmic and 6 or fewer anosmic.

Larger OBV also was associated with larger volumes of areas involved in olfactory processing (including amygdala, hippocampus, insular cortex, and medial orbitofrontal cortex), and OBV largely mediated an age-related association seen between the volumes of the amygdala, parahippocampal cortex, and hippocampus and olfactory function in older participants.

“These findings suggest that OBV holds promise for serving as a novel biomarker that should be routinely measured in individuals with olfactory dysfunction, of advanced age, or who are at risk for neurodegenerative diseases,” wrote Subinoy Das, MD, of the U.S. Institute for Advanced Sinus Care and Research in Columbus, Ohio, in an accompanying editorial.

“A decrease in OBV could warn clinicians about the increased risk for neurodegenerative disease and serve as a marker for therapeutic responses to improve smell,” Das added. “Much more work is needed.”

Prior research has suggested olfactory bulb plasticity. A 2008 study of 20 patients with olfactory loss of duration 3 months to 6 years showed changes in OBV correlated with odor threshold changes. A 2009 review considered extensive evidence that OBV is related to olfactory function in normal and pathologic states, that OBV change parallels degree of dysfunction, and that OBV decreases with duration of olfactory loss.

Olfactory changes are common in multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Hallmark pathology for both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease—neurofibrillary tangles and alpha-synuclein aggregates, respectively—have been demonstrated in the olfactory bulb and more central olfactory functional areas, with bulb involvement among the earliest changes seen.

Symptomatically, a 2011 study found olfactory recognition thresholds were elevated in patients with Parkinson’s disease compared with healthy controls. In a 2019 study of 389 dementia-free Rush Memory and Aging Project participants, impaired olfaction was linked to cognitive decline and was proposed as a marker of neurodegeneration in dementia-free adults.

In the present study, odor identification was worse with age, male sex, and nasal congestion, but was not associated with smoking status. Compared with people who scored 7 or higher on the SIT-12, 26 participants who scored 6 or lower were older (mean age 65.5 versus 53.0) and more likely men (61.5% of those with lower scores versus 42.5% with higher scores).

“Although it is still unclear which factors trigger olfactory bulb pathology in neurodegenerative diseases, viral infections of the olfactory pathway may be implicated,” the researchers observed. “Decreased OBV was recently reported in individuals who had developed anosmia after a SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

“This report, together with findings from the present study, suggest that involvement of the olfactory bulb is likely to be one of the earliest underlying neuroanatomical substrates of olfactory dysfunction,” they continued. “Thus, OBV could be a clinically relevant quantitative marker of early olfactory dysfunction that may prove useful in the identification of individuals who are at an increased risk of several neurodegenerative disorders.”

Limitations of the study included those inherent to cross-sectional studies, such as the lack of ability to assign causation. In addition, smell identification tests were used as a proxy for olfactory function in the study. “Compared with odor threshold and discrimination methods, testing for odor identification is less time consuming and more practical in both the general population and clinical settings,” the researchers noted.

-

Performance on smell identification tests was associated with olfactory bulb volume (OBV), a cross-sectional study found.

-

OBV may serve as a preclinical marker to identify individuals at increased risk for developing neurodegenerative conditions later in life.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Breteler reported no conflicts of interest.

Das reported being the chief medical officer of Tivic Health Inc. He is affiliated with the U.S. Institute for Advanced Sinus Care and Research, which manufactures SmellRegen, an olfactory retraining kit.

Cat ID: 130

Topic ID: 82,130,730,130,361,192,925