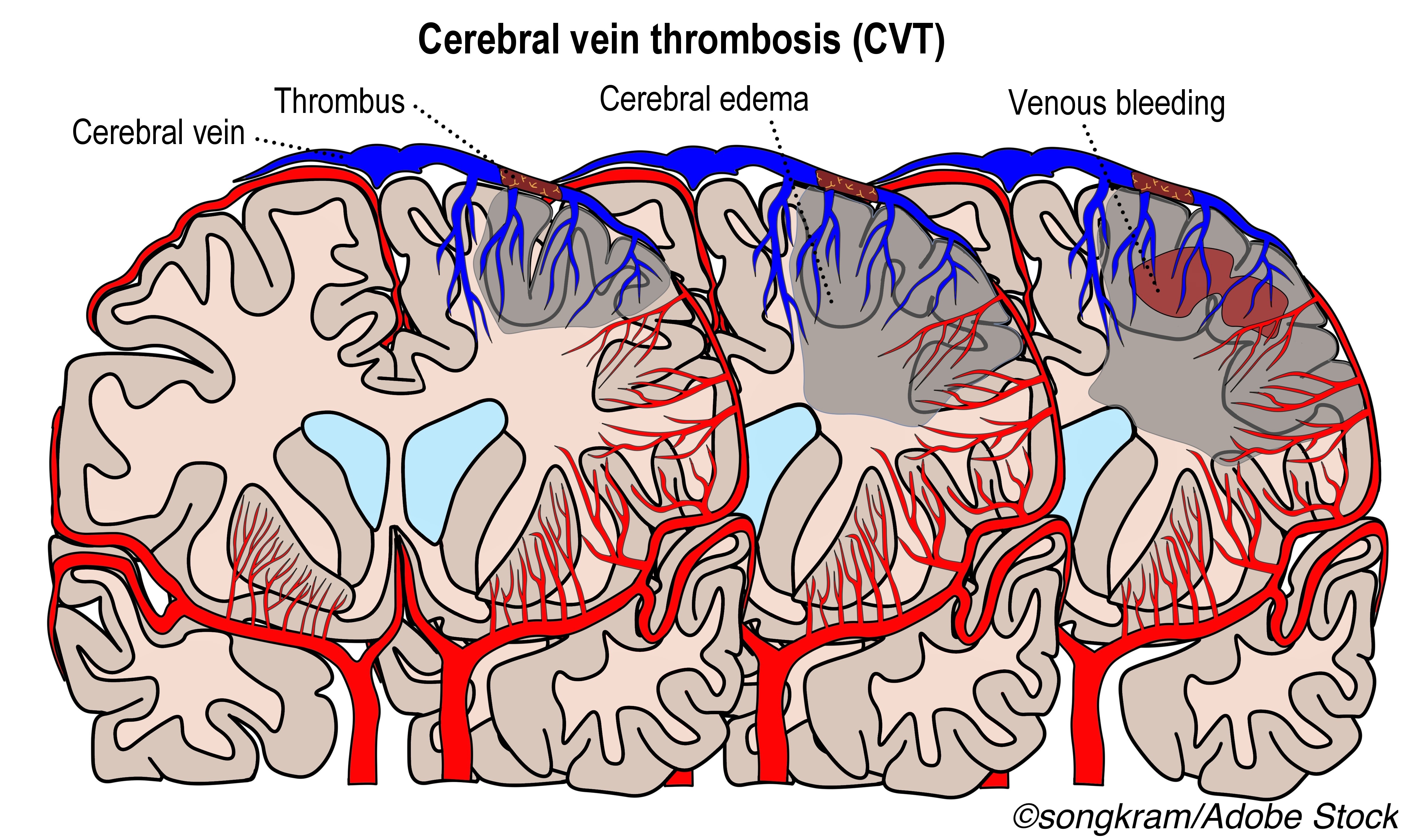

Patients with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) who had seizures within 7 days of diagnosis, compared with CVT patients who had seizures that occurred later, had different seizure predictors with diagnostic and treatment implications, according to two observational reports published simultaneously in Neurology.

“Post-diagnosis acute symptomatic seizures were common, but in absence of pre-diagnosis acute symptomatic seizures, no risk factor sufficiently predicted the development of post-diagnosis seizures to justify primary prophylactic anti-epileptic drug [AED] treatment,” wrote Turgut Tatlisumak, MD, PhD, of the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and co-authors.

“Moreover, the data from our study indicate that, if one would consider prescribing AEDs in patients with CVT, it needs to be administered as soon as possible after the diagnosis, since most patients developed post-diagnosis seizures, including status epilepticus, within 48 hours after diagnosis.”

Acute seizures (7 or less days after diagnosis of CVT) occurred in 34% of the overall cohort. Independent predictors of acute seizures were:

- Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH; adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 4.1 ,95% CI 3.0-5.5).

- Cerebral edema/infarct (aOR 2.8, 95% CI 2.0-4.0).

- Cortical vein thrombosis (aOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.5-2.9).

- Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis (aOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5-2.6).

- Focal neurological deficits (aOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4-2.6).

- Sulcal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH; aOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1-2.5).

- Female-specific risk factors (oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, pregnancy, or puerperium; aOR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1-2.1).

One or more late seizures occurred in 11% of patients, with 46% of those already on an AED. “During a median follow-up of two years, approximately one in ten patients with CVT had late seizure,” Tatlisumak and colleagues noted. “The high recurrence risk of late seizure justifies epilepsy diagnosis after a first late seizure.”

Baseline predictors of late seizures included:

- Status epilepticus in the acute phase (HR 7.0, 95% CI 3.9-12.6).

- Acute seizure(s) without status epilepticus (HR 4.1, 95% CI 2.5-6.5).

- ICH (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1-3.1).

- Subdural hematoma (HR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1-4.9).

- Decompressive hemicraniectomy (HR 4.2, 95% CI 2.4-7.3).

Although 94% received AED treatment after the first late seizure, 70% had a recurrent seizure over two years.

“The cortical location of most CVT infarcts make them theoretically more epileptogenic, and therefore present a stronger case for preventive AED,” wrote Paul Bentley PhD, of Imperial College London, and Pankaj Sharma MD PhD, of the Royal Holloway University of London wrote in an accompanying editorial, but added, “findings from the current studies argue against this, even when stratifying patients on basis of clinical or imaging factors.

“Thus, while certain baseline factors were strongly associated with development of acute or late seizures, the majority of patients with these factors did not develop seizures (e.g. only one-fifth of cases with acute seizures, or one-third of acute status epilepticus, developed late seizures),” they pointed out.

Seizures are an important complication in the acute phase of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), occurring in 20% to 40% of patients, and recurrence risk determines whether epilepsy should be diagnosed after a single late seizure. Diagnosis of epilepsy is recommended after one unprovoked seizure in patients with 10 year recurrence risk of over 60%, but lack of data has led to lack of recommendations regarding the prevention or treatment of late seizures after CVT.

In their study of both acute and late seizures after CVT, Tatlisumak and colleagues analyzed data from the International CVT Consortium, an ongoing 12-hospital collaboration with earliest recruitment of January 1990. They included patients diagnosed with CVT until December 2018, excluding those with prior history of epilepsy.

In the acute seizure study, seizure occurrence was recorded for 7 days after diagnosis. Outcomes were defined as poor if modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores were 2 to 6, and outcome follow-up spanned 12 months. The authors included 1,281 patients (age 40 to 41; women were 67% of those with no acute seizure and 74% of those with acute seizures, P=0.011). Median time from symptom onset to seizure diagnosis was 4 days.

Outcomes at 12 months median follow-up were determined after excluding patients followed up for less than 3 months. A poor outcome was seen in 42% of those with acute seizure and 31% of those without (adjusted OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8-1.4), with no mortality difference (11% versus 9%, respectively; adjusted OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.5-1.3).

In the late seizure study, researchers included 1,127 patients from consortium data after excluding those with a history of epilepsy or less than 8 days of follow-up. Follow-up was for median 2 years. Median time to first late seizure was 5 months.

The dichotomy of a 7-day cutoff between acute and late seizures “parallels seizure classifications in other causes of acute brain injury, including trauma, surgery, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and meningoencephalitis, and mirrors a bimodal distribution in seizure frequency across time, seen after arterial ischemic stroke,” the editorialists noted.

“Across all these diagnoses, general rules emerge: most patients with acute symptomatic seizures do not develop late seizures (making continuing antiepileptic drugs beyond a few months unjustified in most cases); emergence of late seizures portends a high risk of recurrence (i.e. epilepsy, often necessitating long-term AEDs); and the extent of cortical damage, particularly hemorrhage predicts the risk of both early and late seizures. These new studies confirm all three principles for CVT.”

Limitations of the studies include their inability to include more precise data on lesion location. Treatment efficacy was not evaluated. Also, some data were collected retrospectively, and the consortium’s role as tertiary referral center may over-represent severe cases.

-

Patients with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) who had seizures within 7 days of diagnosis, compared with CVT patients who had seizures that occurred later, had different seizure predictors with diagnostic and treatment implications, according to two observational reports.

-

Acute seizures (7 or less days after diagnosis of CVT) occurred in 34% of the study cohort. One or more late seizures occurred in 11% of patients.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Research was supported by the Swedish Neurological Society, Elsa and Gustav Lindh’s Foundation, P-o Ahl’s Foundation, Rune Ulla Amlov’s Foundation, the Swedish Society of Medical Research, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, University of Gothenburg, and the Swiss Heart Foundation.

Tatlisumak reported no disclosures.

Bentley and Sharma reported no disclosures.

Cat ID: 34

Topic ID: 82,34,730,34,192,925