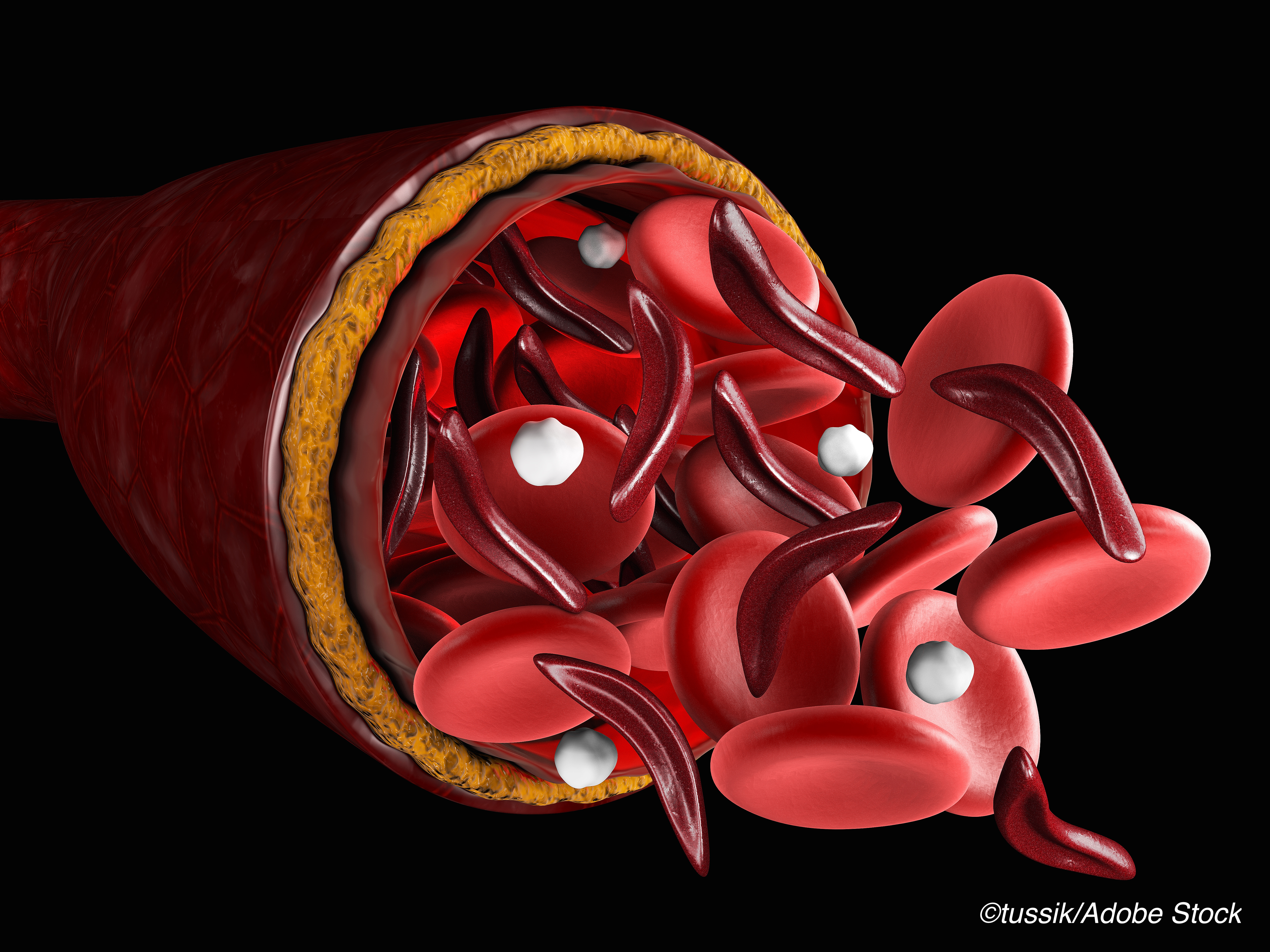

Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) who are experiencing a vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) receive better guideline-adherent pain management at infusion centers (IC) than in emergency departments (ED), a prospective cohort study suggests.

A VOC is a painful, acute medical emergency that is, according to Sophie Lanzkron, MD, MHS, from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and University Hospitals in Cleveland, and colleagues, a common complication of SCD that is “excruciatingly painful” and the “leading cause of hospital and emergency department use.” The ED is typically the place patients seek help.

“We found that patients treated in an IC received parenteral pain medication substantially faster than those seen in the ED,” Lanzkron and colleagues wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Patients seen in the IC were more likely to have their pain reassessed 30 minutes after their initial dose of parenteral medication and substantially less likely to be hospitalized than those who received care in an ED.”

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute made recommendations for the management of acute pain in its 2014 guideline, “including rapid initiation of analgesic therapy within 30 minutes of triage or within 60 minutes of registration and reassessment of pain every 15 to 30 minutes until controlled,” Lanzkron and colleagues wrote.

In their study—ESCAPED (Examining Sickle Cell Acute Pain in the Emergency Versus Day Hospital)—they culled data from a prospective cohort of patients recruited at four sites in the U.S. from April 2015 to December 2016. Of 483 participants enrolled, 269 had acute care visits on weekdays and were included in the analysis. Patients all lived within 60 miles from one of the study sites and were followed for 18 months. Treatment according to the NHLBI guidelines was assessed including how soon were the patients with VOC seen in either an ED or an IC, when was their first dose of parenteral pain medication, and was their pain reassessed after the first medication dose was completed within 30 minutes. Researchers also assessed patient disposition on discharge from the acute care visit at either facility.

“With inverse probability of treatment–weighted adjustment, the mean time to first dose was 62 minutes in ICs and 132 minutes in EDs; the difference was 70 minutes (95% CI, 54 to 98 minutes; E-value, 2.8),” the study authors wrote. “The probability of pain reassessment within 30 minutes of the first dose of parenteral pain medication was 3.8 times greater (CI, 2.63 to 5.64 times greater; E-value, 4.7) in the IC than the ED. The probability that a participant’s visit would end in discharge home was 4.0 times greater (CI, 3.0 to 5.42 times greater; E-value, 5.4) with treatment in an IC than with treatment in an ED.”

Most of the patients in the study were female, mean age was 71, nearly all graduated high school, just over a third were employed, and more than half were insured by Medicaid and had incomes less than $20,000 per year.

Julie Kanter, MD, writing in an accompanying editorial, lauded the study’s methodology, namely the number of patients enrolled, the continuous 18-month follow-up, and that instead of comparing pain scores, Lanzkron et al “used more quantifiable outcomes (such as time to first intravenous opioid and frequency of admissions).” She also noted that the adult participants were all under the care of an SCD specialist.

“Although this may not surprise providers who routinely treat persons afflicted by cancer or cystic fibrosis, there is a paucity of adult-focused SCD specialists in the United States. Recent data suggest that fewer than 30% of affected adults are seeing specialist who can initiate an individualized pain plan or recommend disease-modifying therapy.” Instead, Kanter noted, most patients with SCD are seen by primary care physicians or oncologists who are not SCD experts. Moreover, she added, there is no national funding for SCD centers, so few exist.

Lanzkron and colleagues give several possible reasons SCD patients with VOC fared better at infusion centers than in emergency departments:

- Structural problems in the ED such as overcrowding.

- Emergency physicians’ limited knowledge about the patients they are seeing.

- Inadequate pain management in EDs despite guidelines.

- Experience of IC staff in treating patients with SCD.

Kanter also noted that because care at infusion centers results in fewer hospital admissions, there is also a decrease in hospital-related morbidity and cost.

But the study authors and the editorialist point to other issues beyond place of care that disadvantage patients with SCD—disparity of care and inherent racism.

“…[T]he recent pandemic has revealed the ugly underbelly of the American health care system, in which not all individuals have appropriate access to care or health care coverage,” Kanter wrote. “Sadly, these individuals are most often people of color who are also negatively affected by numerous other social determinants of health. Providers specializing in SCD have always recognized these bitter truths in the health care system and are constantly fighting for ethical, equitable care for our patients. The value in the IC model must be recognized as important because the model offers a better way to manage this horrific disease.”

And the often crowded and beleaguered EDs are not an ideal setting for acute pain management, Lanzkron and colleagues pointed out, as they are fraught with “long delays, lack of efficacy, and conflict.”

The study authors go on to point out that patients with SCD do not feel involved in decision making about their care, and that they are not shown “respect, trust, and compassion” by their providers. They noted that one study “found that 81% [of patients with sickle cell disease] chose to suffer with their pain at home rather than seek care in an ED because of negative ED experiences.”

One of the limitations of the study was that all the patients had uncomplicated VOCs. Another limitation had to do with the fact that patients could not be randomized to either an IC or the ED due to their reluctance to be assigned to ED-only care.

“There is also the ethical and pragmatic challenge of randomizing during an acute VOC event,” Lanzkron and colleagues wrote. “The best way to minimize the threat of residual confounding is to measure a comprehensive set of covariates. We identified and assessed many variables that can affect the severity of the disease.”

-

Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) who are experiencing a vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) receive better guideline-adherent pain management at infusion centers (IC) than in emergency departments.

-

Patients seen in the IC were more likely to have their pain reassessed 30 minutes after their initial dose of parenteral medication and substantially less likely to be hospitalized than those who received care in an ED.

Candace Hoffmann, Managing Editor, BreakingMED™

The primary funding for the study is from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Lanzkron has received consulting fees from Bluebird Bio, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Novartis; and grants from HRSA, NHLBI, Imara, Global Blood Therapeutics, Shire, and Novartis, all of which were paid to her institution.

Kanter reported no disclosures of interest.

Cat ID: 118

Topic ID: 78,118,254,497,730,118,192,925