Personalized medicine is the rallying cry for a new era in clinical medicine—an era in which therapies can be assigned by genotype. But, as compelling as that scenario is as part of a TED talk, it doesn’t always live up to the promise in the real world of clinical medicine.

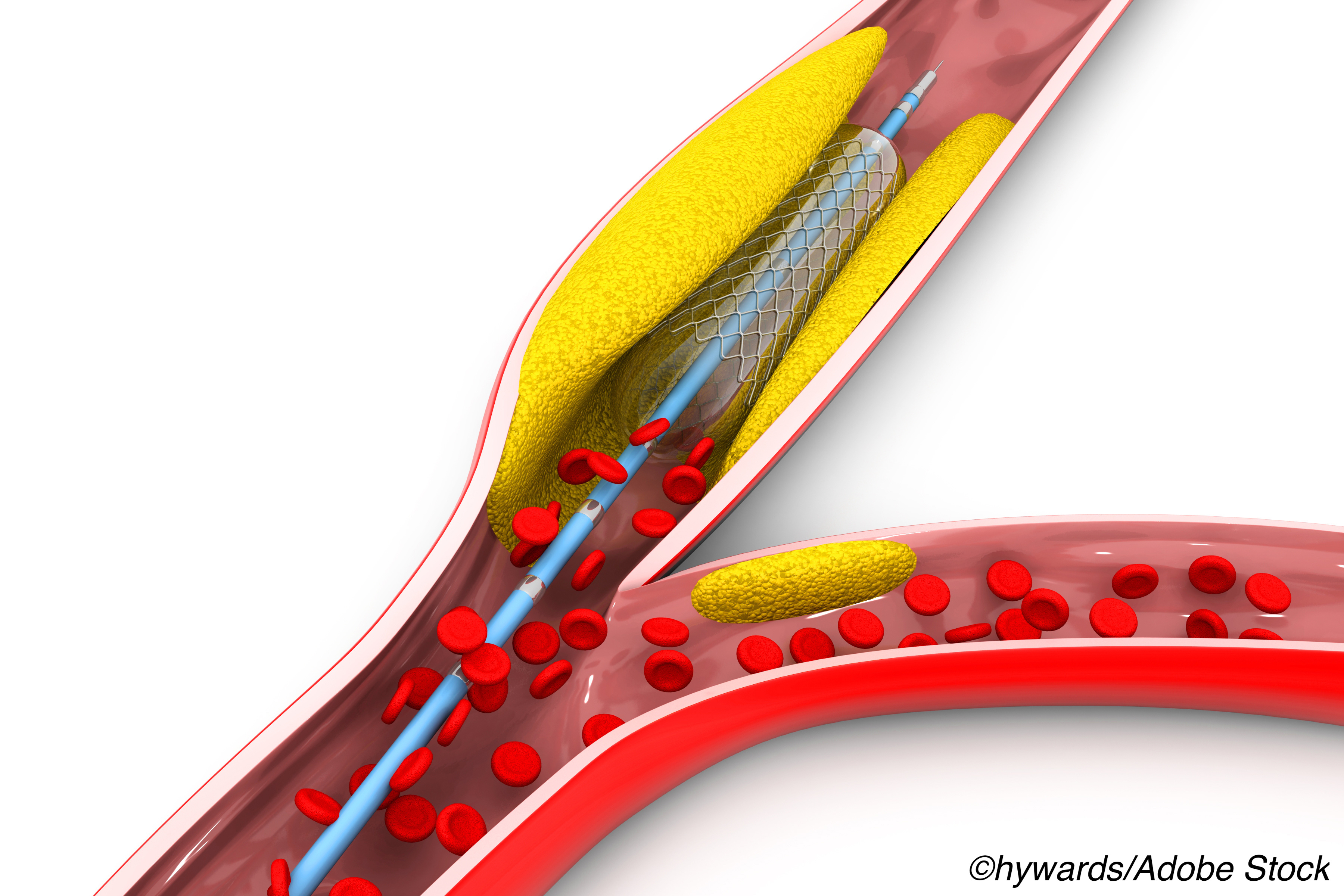

For example, genotyping can identify carriers of CYP2C19 loss of function alleleles (LOF), which suggests that after undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) those patients would have a better outcome if treated with an antiplatelet that targets that CYP2C19 LOF, but in the TAILOR PCI trial it didn’t work out that way.

About half of the 5,302 acute coronary syndrome patients recruited for the trial underwent point-of-care genotyping and based on those results they were assigned to either ticagrelor or conventional treatment with clopidogrel following stenting. The patients who didn’t have point-of-care genetic testing were given clopidogrel but did undergo genotyping after 12 months.

After 12 months there were no fewer major cardiovascular events between patients who had genotype-guided treatment and those who received conventional treatment—even if the presence of CYP2C12 LOF was confirmed at 12 months. The findings reported by Naveen L. Pereira, MD, of the Mayo Clinic and colleagues were published in JAMA.

As disappointing as those results appear at first blush, a trio of cardiologists from the Gill Heart Institute of the University of Kentucky and the Lexington VA Medical Center say while now may not the optimum time genotype-guided treatment, it is also not the time to discard this approach.

“The utility of a personalized medicine approach as attempted by genotyping for drug response should not be abandoned in modern practice,” write David J. Moliterno, MD, Susan S. Smyth, MD, PhD, and Ahmed Abdel-Latif, MD, PhD in an editorial also published in JAMA. “Studies have shown that prasugrel and ticagrelor are associated with higher bleeding risk and are more expensive, prompting physicians to consider de-escalation of antithrombotic therapy early after PCI. In such patients, as well as those at higher risk of bleeding and those receiving triple antithrombotic therapy (i.e., DAPT plus an oral anticoagulant, such as warfarin), a de-escalation strategy could benefit from genotyping or platelet function testing to determine the optimal antiplatelet regimen. The broader question is how much the health care system should invest in integrating these strategies into daily practice and if the return on such an investment is clinically and financially rewarding. Clinicians and patients would argue that the clinical and financial cost of genotype testing would pale in comparison with the cost of an admission for stent thrombosis or a major bleeding complication.

The future is clearly pointing toward a personalized strategy for therapeutic interventions, and genotype-guided approaches should be part of this strategy—the question is how much. However, the clinical evidence at this critical moment of revamping the health care system does not support the routine use of personalized genotype-based selection of antiplatelet therapy for patients with coronary artery disease.”

TAILOR-PCI was an “open-label trial of 5302 patients undergoing PCI for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) or stable coronary artery disease (CAD).” The primary endpoint was the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis, and severe recurrent ischemia at 12 months. The median age of patients was 62 and 25% were women. Most participants (82%) had ACS.

“Of 1,849 with CYP2C19 LOF variants, 764 of 903 (85%) assigned to genotype-guided therapy received ticagrelor, and 932 of 946 (99%) assigned to conventional therapy received clopidogrel,” they wrote.

Among the findings:

- At 12 months 4.0% of patients who received genotype-guided therapy experienced an endpoint event versus 5.9% of patients in the conventional therapy group (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.43-1.02, P =0.06).

- Major or minor bleeding events occurred in 1.9% of the genotype-guided group versus 1.6% of the conventional treatment group (HR, 1.22, 95% CI 0.60-2.52 P =0.58).

“The test of the proportional hazards assumption was significant (P = .03), suggesting that the assumption may not hold; this was further supported by graphical displays. Therefore, a post hoc analysis was performed that demonstrated an estimated HR for the CYP2C19LOF genotype-guided therapy group as compared with the conventional therapy group of 0.21 (95% CI, 0.08-0.54; P = .001) at 0 to 3 months’ follow-up, 0.78 (95% CI, 0.38-1.61; P = .50) at 3 to 6 months’ follow-up, and 1.44 (95% CI, 0.69-3.03; P = .33) at 6 to 12 months’ follow-up,” Pereira and colleagues wrote.

They noted that their trial was the first to “prospectively address the potential utility of genotype-guided oral P2Y12 inhibitor therapy as compared with conventional therapy”.

But they cautioned that the findings should be “interpreted in the context of the treatment effect (50% reduction in ischemic events) that the study was powered to detect based on the prespecified analysis plan.” That was actually a limitation since the trial was underpowered to detect “an effect size less than the 50% relative reduction ….”

Additionally, they noted that the “potential effect of a precision medicine approach may be more important early after PCI, as suggested in the post hoc analysis that demonstrated the potential benefit of genotype-guided oral P2Y12 inhibitor therapy in the first 3 months after PCI, and may question the 12-month duration of follow-up in this trial to demonstrate the efficacy of such an approach.”

-

Be aware that selection of an oral P2Y12 inhibitor based on genotype did not reduce the relative risk of major cardiovascular events following stenting.

-

The findings from this randomized trial suggest that 12-month outcomes in patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles do not appear to be affected by choice of oral P2Y12 inhibitor.

Peggy Peck, Editor-in-Chief, BreakingMED™

Funding for this research was provided by the NIH.

Pereira reported receiving grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Moliterno, Smyth, and Abdel-Latif had no disclosures.

Cat ID: 306

Topic ID: 74,306,730,306,192,925