The 2017 McDonald criteria for diagnosing multiple sclerosis (MS) were more sensitive but less specific than the 2010 criteria in predicting clinically definite MS (CDMS) for patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), a retrospective study found.

At 36 months, the 2017 criteria had higher sensitivity (83% versus 66%), lower specificity (39% versus 60%), and similar accuracy (area under the curve values of 0.61 versus 0.63) compared to the 2010 criteria, reported Massimo Filippi, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy, and co-authors wrote in Neurology. The newer criteria also shortened the time to diagnosis substantially over the 2010 version, with a median time to MS diagnosis of 3.2 months versus 13 months, respectively.

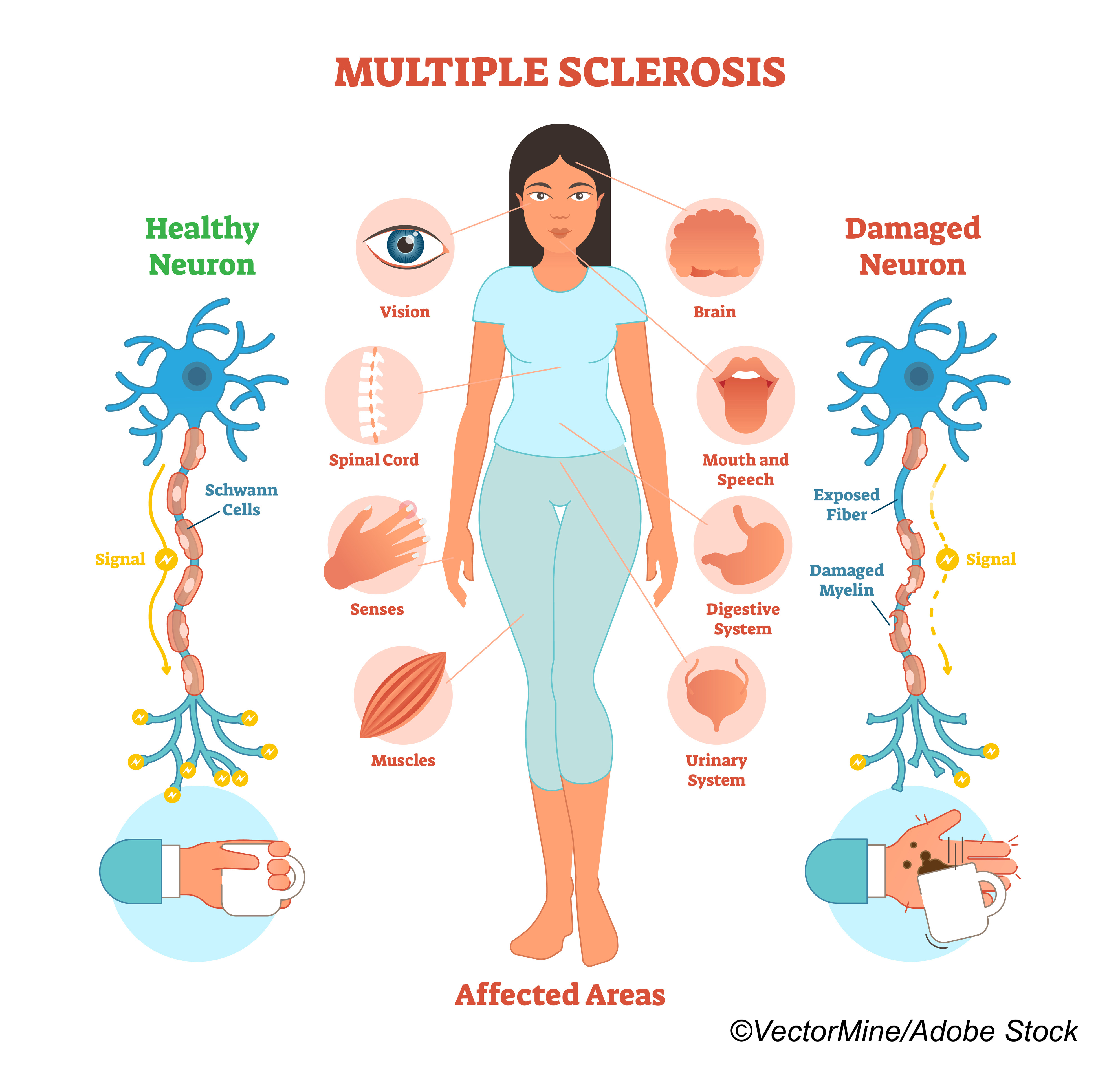

CIS is an episode suggestive, but not diagnostic, of MS. If there is a second suggestive episode, the diagnosis is changed to clinically definite MS, though data from imaging and laboratory studies also can satisfy diagnostic criteria for MS.

One change with the 2017 McDonald criteria was that the presence of oligoclonal bands in spinal fluid allowed MS to be diagnosed without clinical or MRI evidence of dissemination in space. “This validation study extends previous studies, which are characterized by high between-study variability performance of the different criteria,” Filippi and colleagues noted. “We confirmed that the inclusion of oligoclonal band assessment increased the sensitivity, reducing the specificity, while preserving the accuracy of the criteria.”

“Although the performance of the 2017 McDonald criteria seems slightly worse in the short term than the 2010 McDonald criteria, due to a lower specificity, the overall accuracy increases over time, thus the presence of oligoclonal bands contributes to correctly identify patients developing CDMS when longer follow-up are considered, underlying the relevance of longer evaluation to better evaluate the performance of the diagnostic criteria,” the researchers continued.

“The progressive improvement of criteria performance with time could be due to the effects of disease modifying therapies that, if started, may delay the occurrence of a second event, thus negatively influencing the specificity of the criteria when the follow-up is limited to a few years,” they added.

The researchers reported on 785 CIS patients recruited between June 1995 and October 2020 from European MAGNIMS network MS centers. They obtained imaging and spinal fluid data within 5 months of the qualifying episode of CIS, and follow-up MRI within 15 months.

The median age of onset in participants was 32, and 68% were women. At the last evaluation (median of 69.1 months), 406 patients (52%) had a second clinical episode, which changed their diagnosis to CDMS.

Median time to MS diagnosis after a first CIS episode for the 2017 McDonald criteria with and without oligoclonal bands were 3.2 and 11.4 months, respectively. For the 2010 McDonald criteria, median time to diagnosis was 13.0 months; for MS diagnosed by a second suggestive episode (CDMS), it was 58.5 months.

The performance of the 2017 and 2010 McDonald criteria at month 60 was comparable to what was seen at month 36.

“In our study, the 2017 McDonald criteria shortened the median time to MS diagnosis by 4.6 years compared with the clinical criterion alone and by 10 months compared with the 2010 McDonald criteria,” Filippi and co-authors wrote. “This has substantial implications in the management of CIS patients. An earlier MS diagnosis may facilitate earlier treatment, with beneficial effects on MS prognosis, since therapies have demonstrated to reduce the risk of CDMS conversion roughly by 30-55% and could exert long-term benefits to CIS patients.”

The 2001 McDonald criteria were the first to include imaging requirements which, along with subsequent criteria revisions in 2005, 2010, and 2017, have led to shorter time to MS diagnosis and earlier treatment, noted Gary Cutter, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Marcus Koch, MD, PhD, of the University of Calgary, Canada, in an accompanying editorial.

“But these criteria are not perfect,” Cutter and Koch observed. “While the majority of patients with CIS develop clinically definite MS, some never experience another clinical demyelinating event and thus would not be considered to have CDMS.”

“The paper by Filippi et al shows the success of the revised criteria doing what they do best, but more consideration must be given to the inevitable tradeoff of lowered specificity that comes when you increase sensitivity,” the editorialists wrote.

Lower sensitivity could lead to diagnostic error bestowing a lifelong diagnosis of MS for something that will not lead to relapse or disability, or exposure to unnecessary or inconvenient treatments and their side effects, creating significant costs for patients and the healthcare system, they noted. Moreover, it could distort research and clinical trial results, misidentifying responders to therapy: treatment of false positives will seem successful and drug makers have neither the incentive nor the opportunity to intervene, they added.

“There are no natural advocates for the false positives,” Cutter and Koch pointed out.

“What portion of the population falls into this false positive category? We do not know,” they wrote. “Until we do, each iteration of diagnostic criteria will make it seem like we are moving ahead, when in fact we may be walking in place.”

Limitations of the study include its retrospective nature. In addition, CIS patients came from highly specialized European MS centers and may not be representative of CIS patients in other clinical settings.

- The 2017 McDonald criteria for diagnosing multiple sclerosis (MS) were more sensitive but less specific than the 2010 criteria in predicting MS for people with clinically isolated syndrome, a retrospective study found.

- The 2017 McDonald criteria shortened the median time to MS diagnosis by about 10 months compared with the 2010 McDonald criteria.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Filippi is editor-in-chief of Journal of Neurology and associate editor of Human Brain Mapping and received compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Almiral, Alexion, Bayer, Biogen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, and research support from Biogen Idec, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, and Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA.

Cutter reports serving on data and safety monitoring boards of AMO Pharma, Astra-Zeneca, Avexis Pharmaceuticals, Biolinerx, Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Celgene, CSL Behring, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Green Valley Pharma, Mapi Pharmaceuticals LTD, Merck, Merck/Pfizer, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Holdings, Opko Biologics, Neurim, Novartis, Ophazyme, Sanofi-Aventis, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Teva pharmaceuticals, VielaBio Inc, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), and NICHD (OPRU oversight committee); consulting or advisory boards of Alexion, Antisense Therapeutics, Biodelivery Sciences International, Biogen, Clinical Trial Solutions LLC, Genzyme, Genentech, GW Pharmaceuticals, Immunic, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, Medimmune/Viela Bio/Horizon Pharmaceuticals, Medday, Merck/Serono, Neurogenesis LTD, Novartis, Osmotica Pharmaceuticals, Perception Neurosciences, Protalix Biotherapeutics, Recursion/Cerexis Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron, Reckover Pharmaceuticals, Roche, SAB BIotherapeutics, and TG Therapeutics.

Koch received consulting fees and travel support from Biogen, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, and EMD Serono.

Cat ID: 130

Topic ID: 82,130,730,130,36,192,925