The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) issued a new position paper on consent on acute ischemic stroke treatment, replacing a 1999 position paper and a 2011 policy statement.

The new position statement, published in Neurology, was developed by a joint committee of the AAN, American Neurological Association, and Child Neurology Society. It reviews principles of consent and capacity, the role of surrogates, and issues surrounding specific emergency stroke treatments.

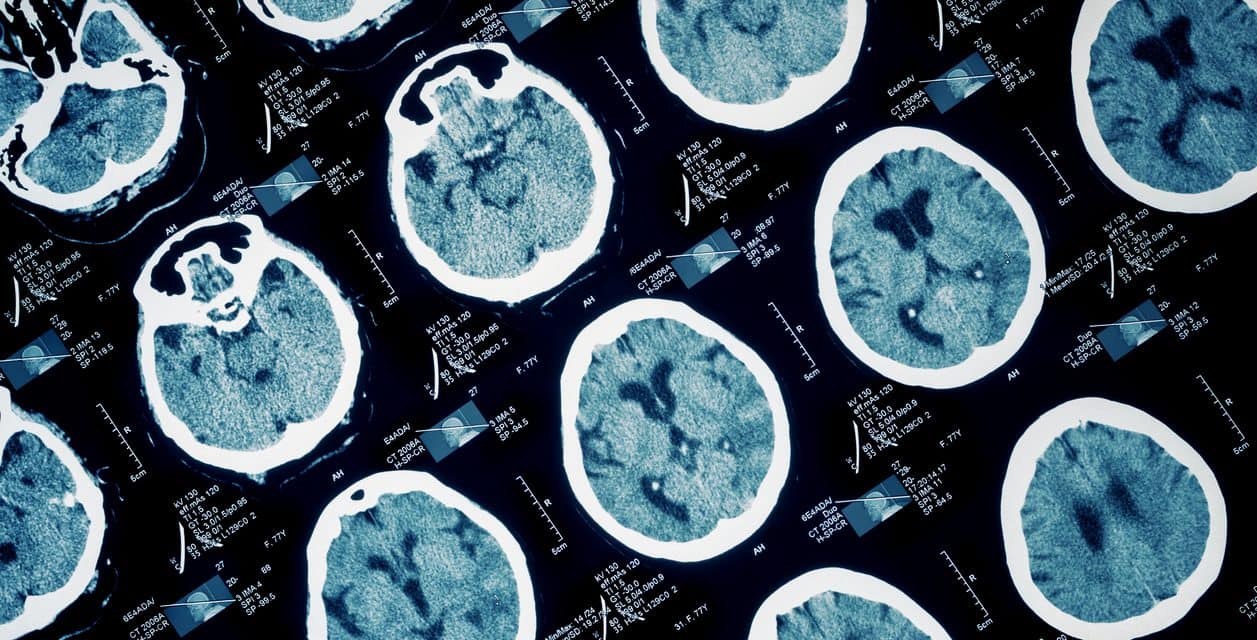

“Stroke treatments that are effective in preserving brain function can only help if administered quickly, sometimes within just a few hours, yet consent for such treatments must often happen when the person who has had a stroke lacks the ability to make decisions and when those who could make decisions for them may be unavailable,” said co-author Justin Sattin, MD, of University of Wisconsin in Madison, in an AAN press release.

“This position statement provides ethical guidance for neurologists on how to navigate the decision-making process for stroke patients when time is of the essence,” Sattin added.

The paper includes a table summarizing basic approaches to ethical decision-making in certain stroke situations. “Neurologists also need to be familiar with the relevant laws in their jurisdictions of practice,” Sattin and co-authors wrote. Several key points from the paper are outlined below.

Consent and Capacity

Informed consent requires that relevant information is communicated, a recommended plan is described, and patient authorization or refusal of that plan is documented.

The capacity to understand and decide includes:

- Understanding the condition being treated and the proposed intervention, which may be assessed by successful patient rephrasing.

- Appreciating how provided information applies to the patient, which may be assessed by having the patient explain why a proposed course may benefit them.

- Reasoning, demonstrated by comparing options and consequences, which may be assessed by asking patients how each option would affect daily life.

- Choice—an expressed decision that is reasonably stable.

“Obtaining informed consent in acute stroke can be encumbered by the sudden, unanticipated, onset of the inability to fulfill one or more of these elements, coupled with the necessity to make decisions rapidly about thrombolysis, thrombectomy, and other high-stakes interventions,” the authors wrote. Cultural perspectives of patients and families also may play a role.

Surrogate Decision-Making

Advance directives can specify whether the patient accepts or rejects a specific intervention, but “instructions in these documents are often either overly specific or too vague, making it difficult to use them to arrive at treatment decisions in the context of acute stroke,” Sattin and co-authors observed. They may address end-of-life scenarios but not debilitating conditions such as acute stroke.

A durable power of attorney designates a surrogate decision-maker, although “many surrogates are inadequately prepared for their role in representing patients’ wishes,” the authors pointed out.

Variable state laws dictate next of kin, hospital ethics committee, or judicial roles when additional consideration is needed. State laws also recognize physician orders outlining acceptable treatment and the scope of guardianship in making treatment decisions.

“Neurologists should be familiar with the laws relevant to these entities in their jurisdictions of practice and, when appropriate, seek legal consultation regarding their application,” Sattin and co-authors advised.

Emergency Stroke Treatment

“There is a rapidly evolving repertoire of treatments that are highly effective in preserving neurologic function after stroke, but only if administered quickly, during a time when patients often lack decisional capacity and surrogate decision-makers may be unavailable,” the authors noted.

In emergency situations calling for rapid treatment for ischemic stroke when a patient lacks capacity, lacks an advance directive, and has no or an unavailable surrogate, “interventions may be provided based on the ethical and common law presumption of consent; that is, the rationale that reasonable people would consent to treatment if they could be asked,” Sattin and co-authors noted. “The imminent risk of significant disability — not just death — also justifies emergent treatment in these circumstances.”

“When surrogates are not present, it may be reasonable to proceed with treatment on the presumption of consent when patients’ cases fit extant inclusion/exclusion criteria, contraindications (particularly, absolute contraindications) are absent, and the overall balance of risks and benefits strongly favors intervention,” they wrote.

The statement reviewed consent in three types of stroke treatments:

- IV thrombolysis with alteplase (Activase): Patient or surrogate should be quickly but clearly informed of the stroke diagnosis and rationale for thrombolytic therapy, prospects for a good functional outcome with and without treatment, and risks of treatment, including intracerebral hemorrhage and angioedema. “When the balance of these risks and benefits is uncertain, and the patient lacks decisional capacity and lacks a surrogate, then the neurologist should adhere more closely to guideline-based inclusion and exclusion criteria,” the authors wrote.

- Neuroendovascular intervention: Large hemispheric strokes for which endovascular therapy is considered are more likely to cognitively impair the patient. “Many of the ethical issues regarding IV thrombolysis are even more pressing in endovascular treatment,” the authors noted. “Patients who meet established criteria for endovascular therapy but who lack both decisional capacity and a surrogate decision maker should be treated on an emergency basis.”

- Decompressive craniectomy: Although it may be lifesaving, decompressive hemicraniectomy for edema due to middle cerebral or internal carotid territory infarctions may leave patients with significant functionally limiting deficits, a trade-off between mortality and major dependency. Those faced with such decisions may take some comfort in the observation that most patients do not retrospectively regret having undergone surgery, even when this results in major disability, the authors noted.

Pediatric Stroke

Given lack of data on efficacy and safety for children, alteplase and mechanical thrombectomy are not FDA-approved and are used off-label in children. The position paper suggests physicians rely on institutional standards and published guidance documents to counsel families and treat children with acute strokes.

Acute Stroke Research

Variable state laws recognize two conditions when patients may be enrolled in research without patient or surrogate consent—research with risk similar to that of daily life, and to permit research on patients requiring emergency intervention whose ability to consent is impaired due to life-threatening conditions.

“Such waivers may be of value in enabling novel trial designs, particularly of systems-level studies addressing the speed and efficiency with which standard therapies are delivered,” Sattin and co-authors noted.

-

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) issued a new position paper on consent in acute ischemic stroke treatment.

-

Stroke treatments that can preserve brain function help only if administered quickly, yet consent for such treatments often must happen when the patient lacks the ability to make decisions and when surrogates may be unavailable.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

The authors reported no targeted funding.

Sattin and co-authors reported no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Cat ID: 38

Topic ID: 82,38,730,8,38,192,925