Circadian dysfunction was linked to the progression of cognitive dysfunction and incident Alzheimer’s dementia, a prospective cohort study suggested.

“Our results indicate a link between circadian dysregulation and Alzheimer’s progression, implying either a bidirectional relation or shared common underlying pathophysiological mechanisms,” reported Peng Li, PhD, of Harvard University, and coauthors in Lancet: Healthy-Longevity.

“Circadian function might serve not only as a biomarker for future risk of Alzheimer’s dementia but also as one that monitors disease progression,” they added. “Whether interventions to optimize or restore circadian rhythms can help prevent or slow the progression of Alzheimer’s dementia or mitigate its related symptoms remains unknown.”

The analysis followed Rush Memory and Aging Study participants, looking at annual cognitive assessments for up to 15 years and four circadian rhythm variables extracted from actigraphy: circadian amplitude (overall strength of circadian rhythm), acrophase (time of daily peak activity), interdaily stability (showing consistency from one day to the next), and intradaily variability (quantifies fragmentation of activity during a day).

Aging was associated with progressive changes; circadian amplitude, acrophase, and interdaily stability progressively decreased over time, and intradaily variability increased over time. The risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia was increased with lower amplitude (HR 1.39 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.19-1.62) and higher intradaily variability (HR 1.22 per 1 SD increase, 95% 1.04-1.43).

Among participants with mild cognitive impairment, an increased risk of Alzheimer’s dementia was associated with lower amplitude (HR 1.45 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.24-1.72), lower interdaily stability (HR 1.21 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.02–1.44), and higher intradaily variability (HR 1.36 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.15-1.60).

A faster transition to Alzheimer’s dementia in participants with mild cognitive impairment was predicted by lower amplitude (OR 2.08 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.53-2.93), decreased interdaily stability (OR 1.35 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.01–1.84), and higher intradaily variability (OR 1.97 per 1 SD increase, 95% CI 1.43-2.79).

Progression of cognitive dysfunction accelerated the aging-related changes seen in the four variables. Annual changes doubled (or more) after diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and doubled again after diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia.

“These observations support the notion that circadian dysfunction, particularly loss of amplitude and fragmentation of daily rhythms, accelerates during the early symptomatic phase of Alzheimer’s disease and can predict impending Alzheimer’s dementia,” wrote Erik Musiek, MD, PhD, of Washington University in St. Louis, in an accompanying editorial.

The findings “provide strong support for the idea that the primary circadian deficit seen early in Alzheimer’s disease is fragmentation of activity rhythms with subtle loss of the difference in activity between day and night,” Musiek wrote. Taken with previous studies of people with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, these results “suggest that subtle fragmentation of circadian rhythms in activity and sleep occur very early in the disease course, perhaps before cognitive changes,” he added.

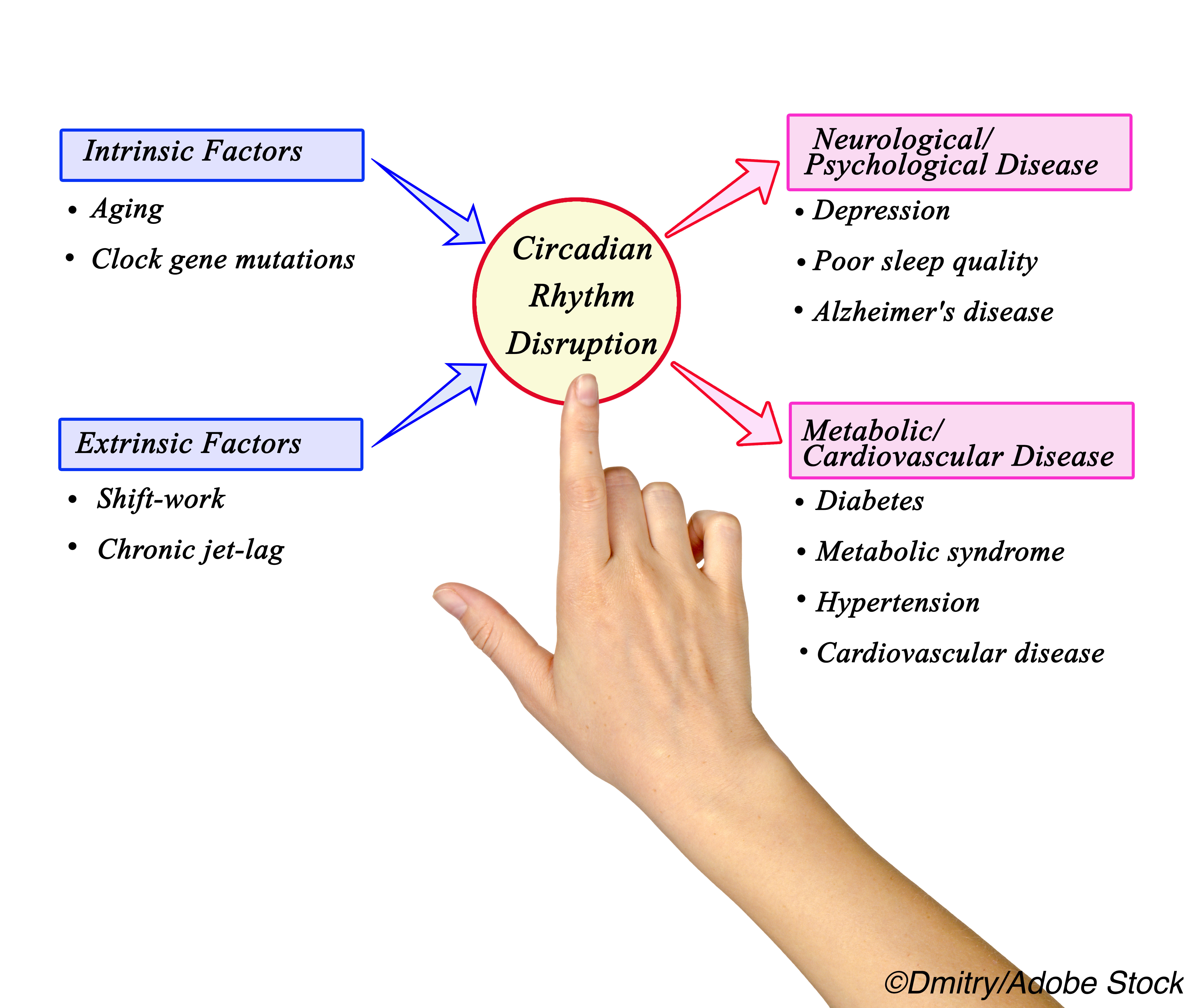

The circadian system coordinates 24-hour rhythms in activity, physiology, and cellular function aligned to global light-dark cycles. Such rhythms decline with age, and those with Alzheimer’s disease have more disruptions in circadian rhythms and the circadian pacemaker (the suprachiasmatic nucleus) than matched controls.

Recent work in people with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease suggests that declines in circadian function can occur early and may be linked to pathogenesis of the disease: a mouse model tied circadian rhythm dysfunction to disruption of daily amyloid-beta oscillations in hippocampal interstitial fluid and to accelerated amyloid plaque accumulation.

In their analysis, Li and colleagues studied data on 1,203 participants who had a median age of 82; 77% were female. One in five (21%) carried the Alzheimer’s risk APOE4 gene.

Alzheimer’s dementia developed in 23% of participants at a mean of 5.8 years after baseline. Of those who were cognitively normal at baseline, 44% developed mild cognitive impairment at mean 4.3 years after baseline. No circadian variables predicted progression from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment.

Annual evaluation included actigraphy — a wristwatch like device on the non-dominant hand for 10 days — and cognitive assessments with a battery of 21 tests.

“The actigraphy-based approach we used is unobtrusive and possesses long-term monitoring capabilities that are scalable to large populations; this method can easily be translated to other observational cohorts to assist in the assessment of Alzheimer’s treatments, as well as identifying individuals at increased risk of Alzheimer’s dementia,” the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the absence of Alzheimer’s biomarkers, which precluded knowing which participants had preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

“Although Li and colleagues have made a large step forward in this area of research, future studies incorporating Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers to define pre-symptomatic patients will be needed to establish whether circadian fragmentation causes Alzheimer’s disease, or vice versa,” Musiek observed.

-

Circadian dysfunction was linked to the progression of cognitive dysfunction and incident Alzheimer’s dementia, a prospective cohort study suggested.

-

The study’s limitations include the absence of Alzheimer’s biomarkers; it assessed Alzheimer’s dementia through annual cognitive testing.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Funding came from the National Institutes of Health and the Bright Focus Foundation.

Li declared no competing interests.

Musiek has worked as a consultant for Eisai Pharmaceuticals.

Cat ID: 33

Topic ID: 82,33,404,485,494,33,361,192,255,925

Create Post

Twitter/X Preview

Logout