What kind of end-of-life care do patients with cirrhosis experience? According to researchers, the treatment goals for patients with decompensated cirrhosis focus on liver transplant and inhibit efforts to provide them with adequate advance care planning throughout the trajectory of illness and to the end of life.

“This finding may explain excessively aggressive life-sustaining treatment that patients receive at the end of life,” Arpan Arun Patel, MD, PhD, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, California, suggested in JAMA Internal Medicine.

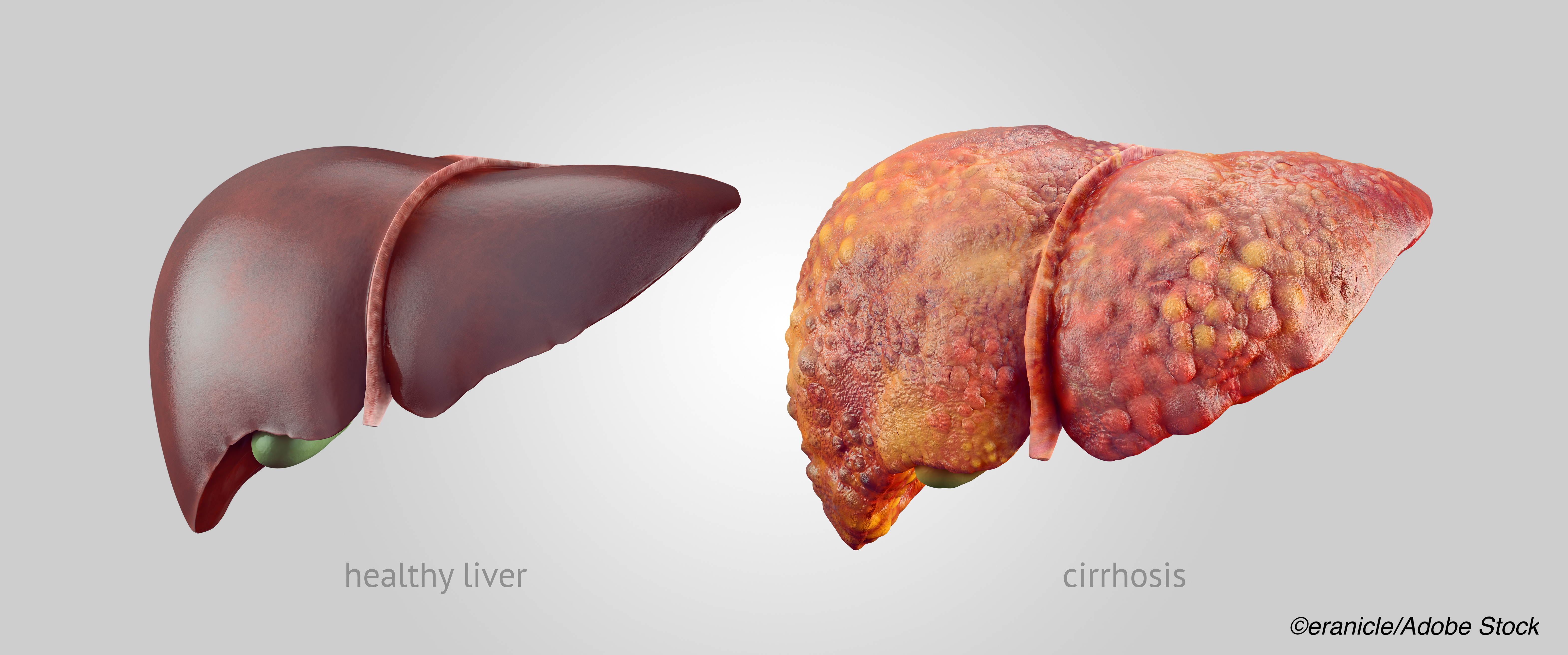

Cirrhosis is a growing cause of mortality in the U.S., with deaths among individuals with cirrhosis increasing by 65% between 1999 and 2016. Thus, Patel and colleagues noted, the issue of end-of-life care among these patients has garnered increased attention.

According to the authors, 60% of patients with cirrhosis die in an inpatient facility, a nursing home, or a long-term care facility — and those with decompensated cirrhosis, characterized by jaundice, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome or variceal hemorrhage, receive care that is particularly burdensome, with more than half mechanically ventilated during terminal hospitalization. Furthermore, the prognosis for these patients is dire, as they have a median life expectancy of approximately two years in the absence of a liver transplant.

While liver transplantation can be successful, it is unavailable to most because of the scarcity of donor organs and the fact that many patients are unsuitable candidates.

Advanced care planning is designed to ensure patients that their care is consistent with their goals, values, and preferences in the context of their prognosis. The authors pointed out, however, that documented advanced care planning is lacking in the case of decompensated cirrhosis, with little evidence available as to why that is so. Here, the authors assessed advanced care planning experiences in liver transplant centers.

Patel and colleagues carried out semi-structured interviews with clinicians and patients from three transplant centers in California. Patients were adults who were diagnosed with cirrhosis, had at least one portal hypertension–related complication, and current or previous Model for End-Stage Liver Disease with sodium (MELD-Na) score of 15 or higher.

The study included 42 patients, as well as 46 clinicians — 13 hepatologists, 11 transplant coordinators, 9 hepatobiliary surgeons, 6 social workers, 5 hepatology nurse practitioners, and 2 critical care physicians. The authors concluded that there were five dominant themes that characterized the advanced care experience for these respondents:

- Consideration of values, goals, and preferences for patients occurred outside outpatient visits.

- Patients’ concerns about the uncertainly associated with their prognosis and the possibility of death were hindered by attitudes of clinicians who urged patients and families to focus on optimistic outcomes.

- Clinician conversations about death were often used as a strategy to change patient behavior.

- Clinicians avoided discussions about non-aggressive treatment options, such as referral to hospice or a do-not-resuscitate code status, because they were contradictory to the goal of transplant.

- Surrogate decisionmakers — often designated beforehand by patients — were unprepared for end-of-life decision-making.

“The uncertainty of a prognosis provides clinicians a chance to counsel patients on the trade-offs required in continuing aggressive care and to elicit a patient’s values and goals in preparation for less fortunate outcomes, but such topics are avoided, although patients view such conversations favorably,” Patel and colleagues found. They also noted that, while social workers are best situated to carry out these conversations, they receive little in the way of support from other members of the transplant team as to how to frame different treatment possibilities and decisions.

“Models of communication that incorporate discussions about preferences for care in future health states if transplant is impossible or unsuccessful can be merged with current communication patterns without disrupting the goal of achieving transplant,” the authors added.

In a commentary accompanying the study, Nneka N. Ufere, MD, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Jennifer C. Lai, MD, MBA, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, noted that clinicians at liver transplant centers have a singular goal – liver transplant. This, they suggested, may prevent them from assessing treatment preferences outside of transplant, leaving patients and their families unprepared and ill-equipped for future decisionmaking.

This study, Ufere and Lai wrote, serves as a call to action for the field of hepatology to invest in developing patient-centered approaches to address current deficits in ACP for patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Future areas of investigation should include the lived experiences of primary caregivers of patients with decompensated cirrhosis, who must often serve as surrogate decision makers early in the disease trajectory when the patient has developed hepatic encephalopathy, experiences that are not unlike those of caregivers of persons with dementia.”

Future interventions should build on the results of Patel et al’s study, “to enhance the illness and prognostic understanding of patients with decompensated cirrhosis and their primary caregivers,” they added. “Such understanding can ensure that patients receive care that is consistent with their goals, values, and preferences over the spectrum of their illness experience and that improves their quality of life and end-of-life care.”

-

Treatment planning for patients with decompensated cirrhosis is almost entirely focused on liver transplant, foregoing advanced care planning discussions of goals, values, and preferences for end-of-life care.

-

The study authors argued that this finding may explain “excessively aggressive life-sustaining treatment that [decompensated cirrhosis] patients receive at the end of life.”

Michael Bassett, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Coauthor Walling reported receiving personal fees from UpToDate for a chapter coauthorship outside the submitted work; Coauthor Sundaram reported receiving personal fees from Gilead, AbbVie, Salix, and Intercept outside the submitted work. The study authors had no other disclosures to report.

Ufere and Lai had no relationships to disclose.

Cat ID: 473

Topic ID: 77,473,570,636,730,473,192,925