Lipid-lowering treatments, including but not limited to statins, have benefit in preventing cardiovascular events in older patients, two papers published simultaneously in The Lancet reported.

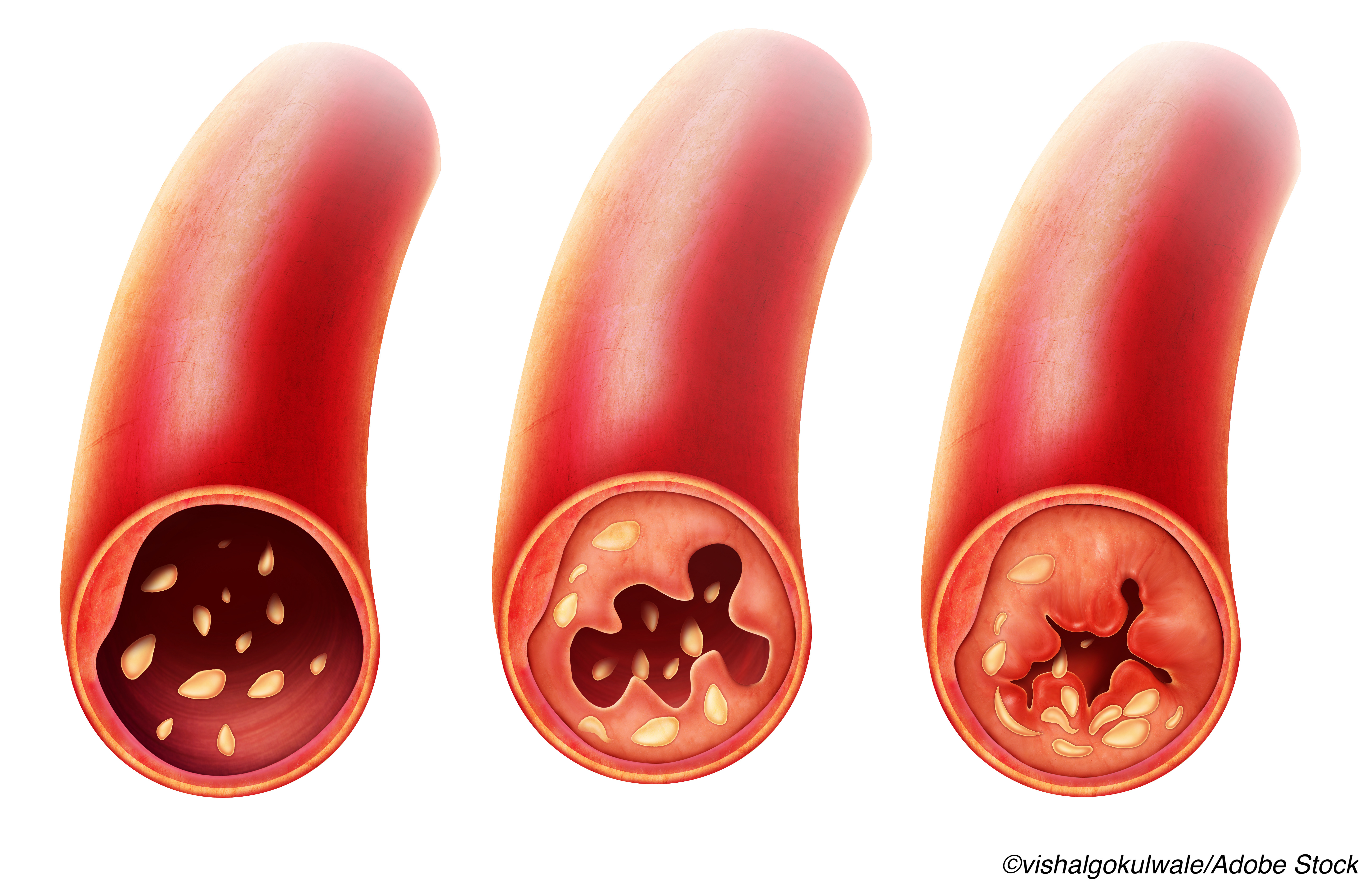

The first paper was an observational study of registry data that found risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular disease was highest in people age 70 and over with elevated levels of LDL cholesterol, compared with younger age groups.

The second paper was a systematic review and meta-analysis that showed LDL cholesterol-lowering therapies, including statins, were as effective at reducing cardiovascular events in people 75 and older as they were in younger people.

Both studies addressed gaps in clinical data for older age groups that had been excluded from some prior trials.

In the observational study, Martin Bodtker Mortensen, PhD, and Borge Gronne Nordestgaard, MD, both of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, studied 91,131 registry patients (13,779 who were age 70-100, and 77,352 who were age 20-69) from the Copenhagen General Population Study cohort. At enrollment in 2003, no one had diabetes or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Risk for MI (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.27–1.41 per 1.0 mmol/L increase in LDL cholesterol) and presence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.12–1.21) were significant in all age groups.

Patients age 70–100 with elevated LDL cholesterol had the highest absolute risk of both MI and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The number needed to treat (NNT) in 5 years to prevent one MI was 1,107 for participants age 20-49, while the NNT was only 80 for people age 80-100. A similar pattern held for preventing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events.

“By contrast with previous historical studies, our data show that LDL cholesterol is an important risk factor for myocardial infarction and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in a contemporary primary prevention cohort of individuals aged 70–100 years,” Mortensen and Nordestgaard wrote.

“By lowering LDL cholesterol in healthy individuals aged 70–100 years, the potential for preventing myocardial infarctions and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is huge, and at a substantially lower number needed to treat when compared with those aged 20–69 years,” they added. “No upper age limit exists at which LDL-lowering therapy ceases to prevent myocardial infarction and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Our data should guide decision-making about whether older individuals will benefit from statin therapy. With the demographic changes seen worldwide with aging populations, our data point [has] a huge potential for reducing the population burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in countries with aging populations.”

In an accompanying editorial, Frederick Raal, MD, and Farzahna Mohamed, MD, both of the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, noted these findings “support the concept of the cumulative burden of LDL cholesterol over one’s lifetime and the progressive increase in risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, including myocardial infarction, with age.”

“Although lipid-lowering therapy was efficacious in older patients, we should not lose sight of the benefit of treating individuals when they are younger,” they pointed out. “Lipid-lowering therapy should be initiated at a younger age, preferably before age 40 years, in those at risk to delay the onset of atherosclerosis rather than try to manage the condition once fully established or advanced.”

The systematic review and meta-analysis, by Marc Sabatine, MD, of Harvard University, and coauthors, included controlled trials of cardiovascular outcomes for any guideline-recommended LDL cholesterol lowering drug in patients 75 or older on a composite vascular event outcome (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or other acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or coronary revascularization) per 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL.

The overall population of the studies reviewed included 21,492 people who were 75 or older; this cohort included patients from trials of statins (55%), ezetimibe (29%), and PCSK9 inhibitors (16%). Per 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL, a 26% reduced risk for the outcome (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.61–0.89; P=0.0019) was seen, similar to that in younger patients.

Benefits were also seen for each component of the composite outcome individually, and results were not significantly different for statin versus non-statin treatments.

“In patients aged 75 years and older, lipid lowering was as effective in reducing cardiovascular events as it was in patients younger than 75 years,” wrote Sabatine and colleagues. “These results should strengthen guideline recommendations for the use of lipid-lowering therapies, including non-statin treatment, in older patients.”

Although the findings encourage the use of lipid lowering therapy in older patients, “however, as with statin therapy alone, no reduction in non-cardiovascular mortality was observed,” the editorialists noted. “Although reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease, which might delay disability from a vascular event and maintain the quality of life, is important, one needs to take this finding into consideration when deciding on prescribing lipid-lowering therapy in older patients.”

Despite a high burden of vascular disease risk, other factors must be balanced against adding medications to reduce LDL cholesterol, given competing factors, including pill burden, polypharmacy, and multiple comorbidities, the editorialists suggested.

“Physician judgment and shared decision-making, taking into account functional status, independence, and quality of life, are therefore important for deciding on the need for lipid-lowering treatment in older patients for both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and one needs to carefully consider whether the benefit will outweigh the risk,” they wrote.

Limitations include predominantly secondary prevention studies that were included in the meta-analysis.

“Whether lipid-lowering therapy should be initiated for primary prevention in people aged 75 years or older is unclear,” the editorialists observed. “The findings of an ongoing trial (STAREE), which is investigating the benefits and risks of lipid-lowering therapy for primary prevention in older patients will be important.”

-

Lipid-lowering treatment, including but not limited to statins, have benefit in preventing events in older patients, a pair of studies reported.

-

Whether lipid-lowering therapy should be used for primary prevention in people age 75 years or older is unclear, and an ongoing trial may be important.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

The observational study received no direct funding. Morternsen received funding from the Lundbeck Foundation.

Tthe meta-analysis and systematic review had no funding. Sabatine reported research grant support through Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Critical Diagnostics, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Genzyme, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, The Medicines Company, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Poxel, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, and Takeda; and personal fees from Alnylam, Bristol Myers Squibb, CVS Caremark, Dynamix, Esperion, Ionis, and EdMyoKardia.

Editorialist Raal reported receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees for advisory board membership, professional input, and lectures on lipid-lowering drug therapy from Amgen, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novartis, and the Medicines Company

Cat ID: 358

Topic ID: 74,358,282,399,402,494,358,4,192,255,925