It’s not “news” that a decline in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is a sign of a failing heart, but a study published in JAMA Cardiology suggests that tracking the directionality of changes in ejection fraction may offer prognostic value.

An LVEF that declines from more than 50% to midrange (<50% → 40%) is a harbinger of poor outcome.

That finding emerged from a cohort study by researchers from the division of cardiovascular medicine at the University of California, San Diego and Siriraj Hospital of Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand.

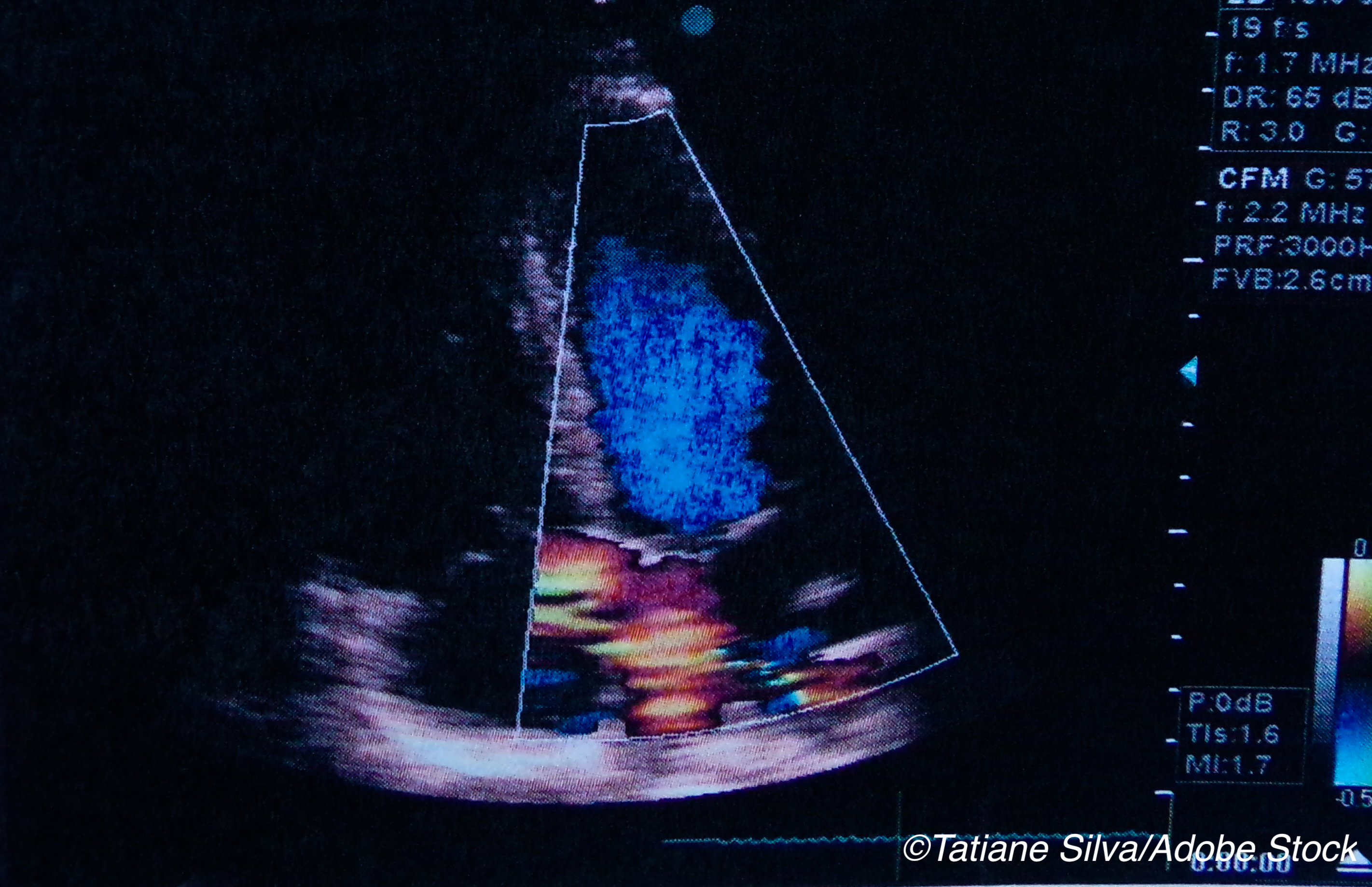

Lead author Alison Brann, MD, and colleagues used electronic health records of patients treated at U.C. San Diego to identify those whose LVEF was 40%-50% as measured by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) done during 2015. All patients had at least 1 prior TTE for comparison. “The clinical course of these patients was then followed from the time of the index TTE through December 2018. Data were analyzed from January to March 2019,” they wrote. The main outcomes were hospitalization, death, and a composite of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalization.

Almost two-thirds of the patients were men (62.1%), and the mean age was 67.4.

“Left ventricular ejection fraction improved from less than 40% in 157 patients (35.0%), deteriorated from greater than 50% in 224 patients (50.0%), and remained between 40% and 50% over time in 67 patients (15.0%). The median (interquartile range) time between the index TTE and the prior TTE was 1226 (570-2995) days, 1159 (419-2884) days, and 1422 (524-2233) days for the improved, stable, and deteriorated groups, respectively,” they wrote.

Among the outcomes:

- There was a 1.34-fold increase (95% CI 1.10-1.82, P =0.03) in risk of the combined endpoint of cause mortality/hospitalization among patients whose LVEF deteriorated.

- There was also a 1.71-fold higher risk cardiovascular death/HF hospitalization (95% CI, 1.08-2.50; P = .02).

“This difference also persisted after multivariable analysis. Increased risk in patients in the deteriorated group for this composite was predominantly due to higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 0.95-3.78; P = .07), as risk of HF hospitalization was not increased. No significant differences in outcomes between patients in the improved and stable groups were seen for any of the end points in either unadjusted or multivariate analysis,” they wrote.

Patients whose LVEF deteriorated were younger and more likely to have a history of chronic kidney disease.

Of interest, HF — diagnosis and/or symptoms — was documented in the electronic health record of “142 of 157 patients (90.4%) in the improved group, 54 of 67 (81%) in the stable group, and 116 of 224 (51.8%) in the deteriorated group (P < .001),” they wrote. “The improved subgroup also had more severe HF symptoms, with a greater prevalence of patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV HF.”

Patients with improved LVEF were more likely to be receiving HF medications including ACE-inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, and diuretics. They were also more likely to implanted devices—ICDs or pacemakers.

“Prior studies have shown that patients with HFmrEF have similar long-term outcomes as patients with either HFrEF or HFpEF,” Brann et al wrote. “While that may be the case for patients with HFmrEF as a group, our findings suggest that their clinical course is strongly influenced by the directional change in LVEF that brought them into the midrange. Notably, patients whose LVEF had deteriorated from greater than 50% were at higher risk of mortality and morbidity than patients whose EF had improved from less than 40%.”

The authors noted a number of limitations, including the reliance on a data obtained from a retrospective EHR review and all the patients were treated at the same large academic institution, which could limit the generalizability of the findings.

“Assessment of LVEF was based on a retrospective review of the LVEF entered in the EHR by multiple readers and is subject to both intraobserver and interobserver variability. This may have affected both the initial categorization of LVEF as well as the changes in LVEF between tests. Inclusion criteria were based on LVEF and did not require that patients have a diagnosis of HF. Additionally, the number of patients in the stable group was relatively small, and this may have precluded our ability to discern significant differences between groups,” they added.

In conclusion, the authors noted that information about prior LVEF is important since it can establish directionality, which should be considered when planning a clinical treatment strategy. Moreover, the findings did confirm the value of guideline-directed medical treatment (GMT) since LVEF improved among the patients who received GMT and those patients had a better outcome.

-

Be aware that directionality of LVEF appears to be an indicator of outcome.

-

In this cohort study, patients who received GMT had a lower risk for hospitalization and/or death.

Peggy Peck, Editor-in-Chief, BreakingMED™

Brann had no disclosures.

Corresponding author Barry Greenberg, MD, has received grants from Rocket Pharmaceuticals and personal fees from ACI Clinical, Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Akcea Therapeutics, Amgen, EBR Systems, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Sanofi, Novartis, Viking Therapeutics, and Zensun.

Cat ID: 3

Topic ID: 74,3,730,3,6,192,916,925