While treatment options for RET-positive NSCLC are few, pralsetinib and selpercatinib may prove beneficial, with good response rates, strong activity, and higher selectivity compared with other multi-kinase inhibitors. This article, originally published Oct. 25, 2021, details the latest results with these agents. Click here to see the original article and obtain CME/CE credit for the activity.

“Oncogenic rearrangements involving RET occur in approximately 1% to 2% of patients with NSCLC [non-small cell lung cancer],” according to Justin F. Gainor, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston.

“RET rearrangements define a distinct molecular subset of the disease,” he told eCancer TV at the 2019 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting. “These patients are typically never smokers, and RET rearrangements don’t really overlap with other oncogenic drivers in lung cancer.”

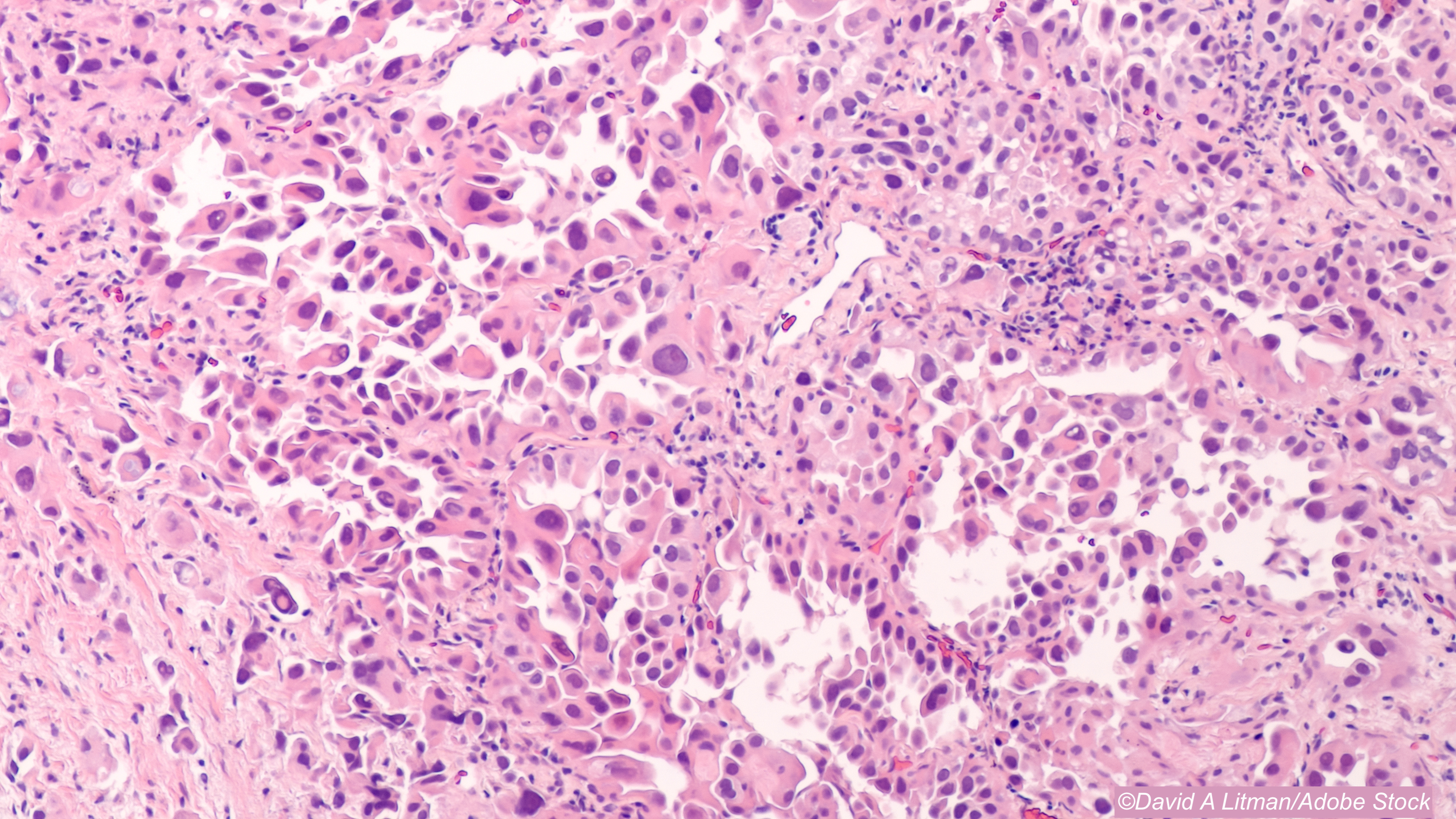

These patients also “tend to have adenocarcinoma histology,” noted Jessica Lin, MD, also of MGH, in a 2020 Society for Translational Oncology YouTube talk.

So, it’s not necessarily surprising that early attempts to treat RET-positive NSCLC with RET non-selective multi-kinase inhibitors were a bit of a bust, noted Alessandro Morabito, MD, of the Istituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS “Fondazione G. Pascale” in Napoli, Italy, and co-authors.

“The weaknesses of these drugs was essentially due to their poor anti-RET potency and to their off-target side-effects, resulting in limited clinical activity burdened by excessive toxicities,” they wrote in a review in Cancers.

On the other hand, selective RET inhibitors, such as the FDA-approved selpercatinib (Retevmo) and pralsetinib (Gavreto), have offered singular results in this singular patient population, and both received high marks from Morabito’s group. “As one of the most selective RET inhibitors, selpercatinib represents a step forward for the management of RET+ lung cancer patients who have been traditionally treated with standard of care therapies,” they wrote.

The LIBRETTO-001 trial set the foundation for selpercatinib as a treatment option in RET-positive NSCLC, Morabito and co-authors said. Many trial patients were heavily pre-treated, yet the ORR came in at 64% (95% CI 54% to 73%), with a median duration of response of 17.5 months (95% CI 12 to not estimable months). Notably, “responses were observed regardless of the RET fusion partner… [t]o date, at least 12 fusion RET partner genes have been identified, the most common being KIF5B and CCDC6 (70-90% and 10-25% of all cases, respectively),” they added.

In the treatment-naive arm of the trial, “the response rate is better—85%—but we don’t [yet] have an estimation of the median PFS [progression-free survival] or the median duration of response,” LIBRETTO-011 investigator Benjamin Besse, MD, PhD, of the Gustave Roussy Cancer Institute in Paris, told VJOncology during the 2021 ASCO virtual meeting, where trial results were updated. However, he reported that in this group, the 2-year overall survival (OS) came in at 88%.

As for pralsetinib, the “small molecule that strongly inhibits the RET kinase domain… displays a strong activity against common oncogenic RET alterations… [and] also has an 88-fold higher selectivity against RET over VEGFR2 compared to what was observed with other multi-kinase inhibitors,” explained Morabito’s group.

They highlighted the phase I-II ARROW trial as one of interest, and early ARROW results released in July 2021 supported the agent as a “well-tolerated, promising, once-daily oral treatment option for patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC,” wrote Gainor, Besse, and co-authors in The Lancet Oncology.

In ARROW, patients (majority ages 60 to 65; 50%-52% female; 53%-59% White; about 34% Asian) received 400 mg once-daily of oral pralsetinib and were allowed to stay on-treatment until disease progression, intolerance, withdrawal of consent, or investigator decision. Trial primary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR) and safety.

In the 71-site international trial, an ORR was seen in 61% (95% CI 50-71) of patients (n=53) with previous platinum-based chemotherapy, including 6% with a complete response (CR). ORR also was seen in 70% (95% CI 50 to 86) of treatment-naive patients (n=19), including 11% with a CR.

For adverse events (AEs) in all 233 trial patients, common grade ≥3 treatment-related AEs were neutropenia (18%), hypertension (11%), and anemia (10%), but there were no treatment-related deaths in the study.

While these phase I/II ARROW results led to accelerated FDA approval for the agent in 2020 for metastatic RET fusion-positive NSCLC (in conjunction with the companion diagnostic Oncomine Dx Target [ODxT] Test), Gainor’s group cautioned that “the findings presented here [in The Lancet Oncology] are interim analyses; at the time of enrolment cutoff, target enrolment had not yet been reached.”

As of October 2021, ARROW continues to recruit patients, with an estimated primary completion date of December 2021 and an estimated study completion date of February 2024.

A study out of China presented at the 2021 World Conference on Lung Cancer focused on Chinese patients in ARROW, and “[t]his study confirmed for the first time the efficacy and safety of pralsetinib in Chinese patients with RET fusion-positive NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy,” commented ARROW investigator Qing Zhou, MD, PhD, Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute in Guangzhou, in a press release. “Pralsetinib has the potential to address unmet medical needs for these patients and may become the first selective RET inhibitor in China.”

That’s important, because RET fusions “may differ between Asian and non-Asian populations,” said Morabito’s group, citing a 2012 study that analyzed 936 tumor specimens from Chinese patients who underwent surgery for early-stage NSCLC and showed that RET-positive patients tended to be younger (ages ≤60) than those with EGFR mutations (72.7% vs 47.8%, P=0.131), along with having more poorly differentiated disease versus patients with other oncogenic drivers.

Other trials of pralsetinib are in the works, such as AcceleRET-Lung and NAUTIKA1, as are studies of selpercatinib (LIBRETTO-431 and 432LUNG-MAP). There are also up-and-coming agents, alectinib (Alecensa) and brigatinib (Alunbrig), which are being tested in the B-FAST and ROME trials, respectively.

And research with non-selective RET inhibitors is ongoing, although with mixed results, Morabito and co-authors pointed out. Trials of cabozantinib (Cabometyx), vandetanib (Caprelsa), and lenvatinib (Lenvima) have offered up ORs that ranged from 3% to 47%, but the agents’ true success may lie in being combined with each other, they added, noting that “[p]reclinical studies have suggested that EGFR signaling could play a central role in reducing RET inhibitors’ efficacy in NSCLC cell lines, thus providing a rationale for co-targeting both EGFR and RET in order to reduce the onset of drug resistances.”

Morabito’s group put forth a number of questions that, hopefully, all of these trials will provide for: “What is the best RET inhibitor for patients with advanced NSCLC and what will be their impact on overall survival? Are there alternative strategies to improve these results, such as combining anti-RET TKI with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or other TKIs [tyrosine kinase inhibitors]? How is it possible to face the resistance mechanisms for RET inhibitors?”

Finally, they suggested that “an interesting future field of investigation would be the further exploration of an upfront combination strategy using either pralsetinib or selpercatinib.”

Shalmali Pal, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Morabito reported relationships with MSD, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Boehringer, Pfizer, Roche, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Takeda, and Eli Lilly. Co-authors reported relationships with, and/or support from, MSD, Qiagen, Bayer, Biocartis, Incyte, Roche, BMS, Merck, Thermofisher, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astrazeneca, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Sysmex, the International Quality Network for Pathology (IQN Path), and the Italian Cancer Society (SIC).

ARROW was funded by Blueprint Medicines. Some co-authors are company employees.

Gainor reported relationships with, and/or support from, BMS, Roche/Genentech, Merck, Takeda, LOXO Oncology/Lilly, Blueprint Medicines, Oncorus, Regeneron, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, Moderna, Novartis, Alexo, Tesaro, Jounce, Adaptimmune Therapeutics, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Besse reported relationships with, and/or support from, AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Blueprint Medicines, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Cristal Therapeutics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Inivata, Janssen, Onxeo, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Takeda, Tolero Pharmaceuticals, 4D Pharma, Aptitude Health, and Cergentis. Co-authors reported relationships with, and/or support from, multiple entities including Blueprint Medicines.

Cat ID: 24

Topic ID: 78,24,730,24,192,65,925

Create Post

Twitter/X Preview

Logout