When the findings of the PARAGON-HF trial were reported at the European Society of Cardiology 2019 Congress in Paris, the disappointment among heart failure specialists was palpable: sacubitril/valsartan, which wowed ESC crowds in 2014 as a therapy “destined to change the management of heart failure” with positive results in the PARADIGM-HF trial of patients with reduced ejection fraction, failed to demonstrate benefit in preserved ejection fraction heart failure.

When a tree falls in a forest and no one is around, it may or may not make a sound, but when a major heart failure trial misses its endpoint—especially by a margin as narrow as seven patients—the resounding thud reverberates around the globe and is the trigger for rigorous, ongoing analyses, which often bear fruit.

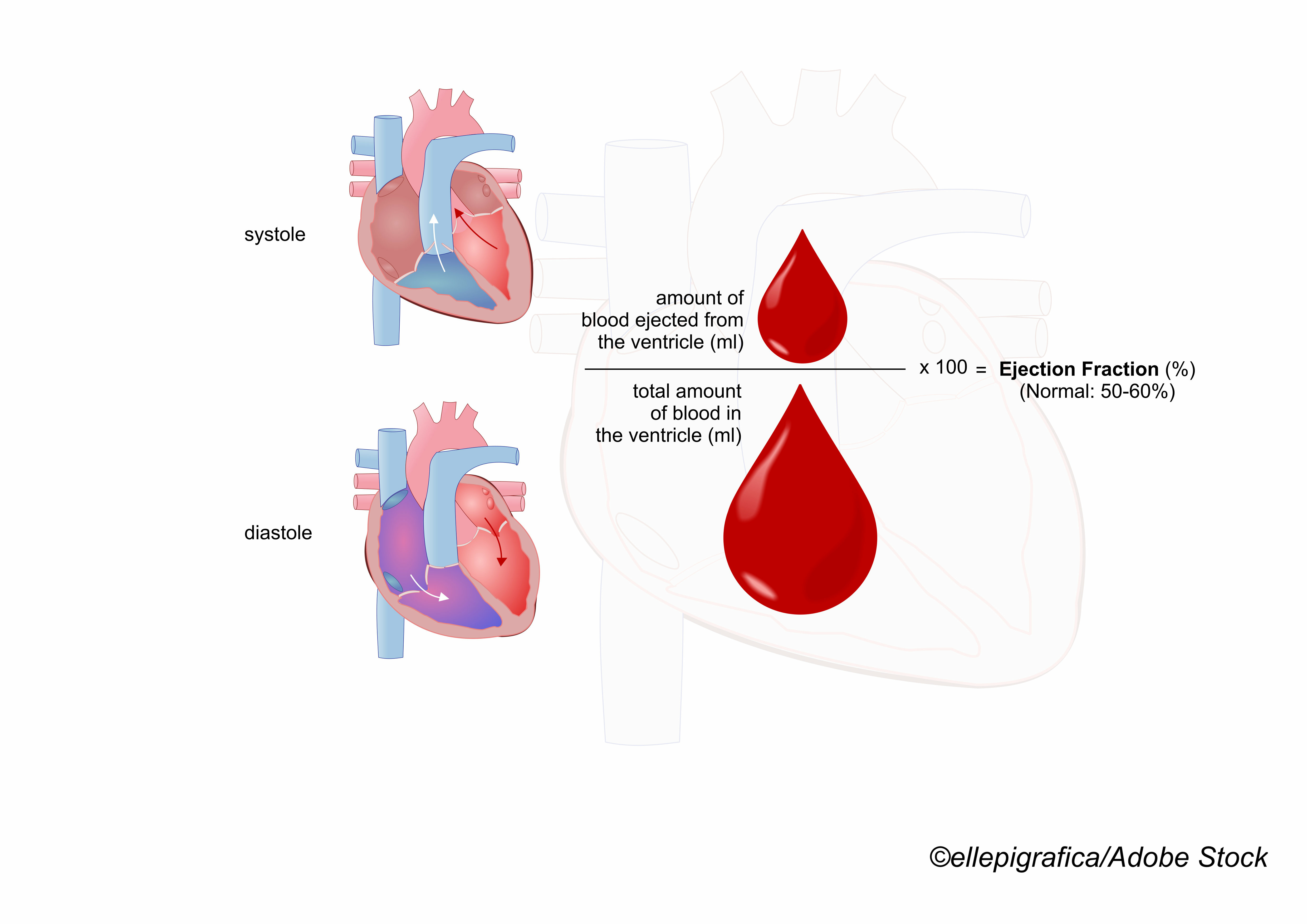

In the case of PARAGON-HF, the fruit was delivered by the Food and Drug Administration, which reviewed the additional analyses and decided to expand the label indications for sacubitril/valsartan to include heart failure patients with LVEF in the range of 41% to 60%, an increase from the 41% to 50% of the original label.

Using a number needed to treat (NNT) formula derived from the PARAGON-HF trial, Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, of the division of cardiovascular medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, and colleagues calculate that if the 1.8 million patients now eligible for treatment with sacubitril/valsartan take the drug, an estimated 180,000 worsening heart failure events—death and/or hospitalizations—will be prevented. They reported the results of their analysis in JAMA Cardiology.

In an editorial that accompanied the study, deputy journal editor Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, wrote, “nontrivial questions remain: are the secondary data from the PARAGON-HF trial, clearly quite provocative, still subject to a statistical play of chance? Will patients with heart failure and an LVEF less than 0.57 actually experience the suggested magnitude of benefit from sacubitril/valsartan for symptomatic heart failure observed in the secondary analysis of the PARAGON-HF trial? Will clinicians have confidence in these expectations? And are there unintended consequences of using secondary analyses, regardless of strength, to expand treatment indications?”

Vanduganthan and colleagues estimated newly eligible patients by “mapping the LVEF distribution from 559,520 adult patients hospitalized between 2014 and 2019 in the Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure registry to adults self-identifying with HF in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2015 to 2018).”

The mean age of patients in the registry was 66 and 42.6% were women, which is of interest because the original PARAGON-HF suggested a trend for benefit among women.

“The potential number of adults projected to be newly eligible varied by the definition of FDA labeling of lower than normal LVEF from 643,161 (95% CI, 534,433-751,888; LVEF of 41%-50%) to 1,838,756 (95% CI, 1,527,911-2,149,601; LVEF of 41%-60%),” they wrote.

Using the PARAGON-HF NNT calculation—treating 7 to 12 patients would reduce one worsening HF event—they wrote that they could empirically estimate that the expanded label indication would postpone or prevent 182,592 worsening heart failure events, more than two and a half times the estimated number of worsening events reduced when sacubitril/valsartan treatment was limited to EFs of 50% or less.

“It has been posited that given the higher average LVEF in women than men, the cutoff to define lower than normal LVEF should similarly be higher in women. Our data indicate that more men are estimated to have prevalent HF in the US, and a greater number were previously eligible for sacubitril/valsartan. In contrast, applying sex-specific cutoffs would greatly expand the number of women who become eligible under revised FDA labeling. In the PARAGON-HF trial, heterogeneity in treatment effects by sex was observed with greater benefits seen in women,” they wrote. “In addition, women appeared to derive benefits from sacubitril/valsartan at a higher LVEF range than men. Given these amplified benefits, only 5 women need to be treated for 3 years to prevent a worsening HF event, while 18 women would need to be exposed to sacubitril/valsartan over 3 years to result in a hypotensive episode (any SBP less than 100 mm Hg). If broadly implemented among newly eligible women with HF, more than 200,000 worsening HF events may be averted over 3 years; these projected figures are 14-fold the number of events potentially averted if sacubitril/valsartan was fully used among newly eligible men. While sex was a prespecified subgroup in the PARAGON-HF trial and although similar 2-way interactions with sex and LVEF have been described with other therapies in individuals with HFpEF these findings require validation, and their implications for clinical practice remain uncertain.”

In his editorial, Yancy concluded that the FDA’s decision to expand the label indication suggests an evolving evidence bar—but he had some cautions.

“What should not evolve, however, are guiding principles of the FDA. The FDA wields considerable regulatory authority and sets the standard for evidence of benefit but also owns the important responsibility to assess safety. It is imperative that standards for safe and effective, the long-held ethos of the FDA, remain the basis for all drug indications,” he wrote.

“Clearly, the exploratory data analyses of the PARAGON-HF trial are intriguing, made even more intriguing by review of the results as a function of sex (outcomes in women compared with men: rate ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90; P<.006),” Yancy added. “The urgency of need for effective therapies for HFpEF cannot be discounted, and it is likely that sacubitril/valsartan is a new therapy for certain patients with HFpEF. Clinical implementation will resolve any residual uncertainties and will test the integrity of this evolved FDA evidence bar. Unfailingly, the correct approach remains further discovery science, but for now, a new, reasonably evidence-based therapy in HFpEF emerges, and for those patients with both the morbidity and mortality risks of HFpEF, hope is palpable.”

-

An FDA-approved label change for sacubitril/valsartan to add an indication for persons with LVEF of 60% or lower increased the number of adults who are eligible for this ARNI therapy, which may prevent close to 180,000 worsening heart failure events.

-

The potential number of adults projected to be newly eligible varied by the definition of FDA labeling of lower than normal LVEF from 643,161 to 1,838,756, according to the study authors.

Peggy Peck, Editor-in-Chief, BreakingMED™

The PARAGON-HF trial was sponsored by Novartis. The Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure program is provided bythe American Heart Association and is sponsored, in part, by Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly Diabetes Alliance, NovoNordisk, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, and Bayer.

Vaduganathan has received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees for serving on advisory boards for American Regent, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter International, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Relypsa, and Roche Diagnostics; and personal fees for speaking for Novartis and Roche Diagnostics; and participates on clinical end point committees for studies sponsored by Galmed and Novartis.

Yancy’s spouse receives salary support from Abbott Laboratories.

Cat ID: 3

Topic ID: 74,3,730,3,192,925