There’s still not enough evidence to truly assess the pros and cons of general screening for atrial fibrillation (AFib), according to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

Karina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc, of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York City, and co-authors laid out the multiple shortcomings of AFib screening in asymptomatic adults (ages ≥50) that led to the “I” (insufficient) grade recommendation in JAMA:

- Detection: There is “[i]nadequate evidence to assess whether 1-time screening strategies identify adults 50 years or older with previously undiagnosed AFib more effectively than usual care.”

- Benefits of early detection, intervention, and treatment: There is “[i]nadequate direct evidence on the benefits of screening for AFib” and “on the benefits of treatment of screen-detected AFib, particularly paroxysmal AFib of short duration.”

- Harms: There is “[i]nadequate direct evidence on the harms of screening for AFib.”

However, Davidson’s group conceded that there was “[a]dequate evidence that intermittent and continuous screening strategies identify adults 50 years or older with previously undiagnosed AFib more effectively than usual care,” and that there is “[a]dequate evidence that treatment of AFib with anticoagulant therapy is associated with small to moderate harm, particularly an increased risk of major bleeding.”

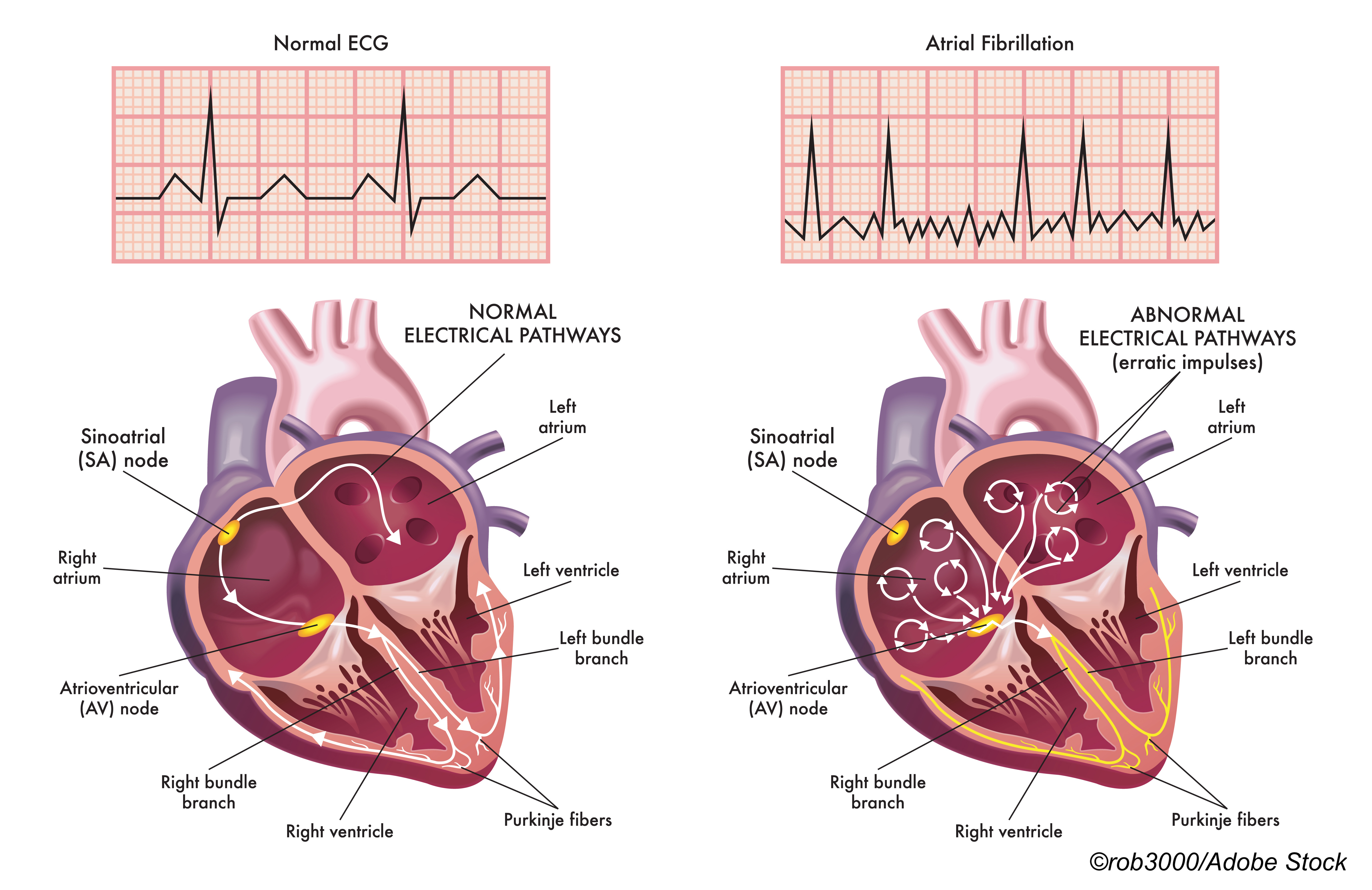

For this update, the task forced considered a host of cardiac screening methods, such as automated blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximeters, smartwatches, and smartphone apps, but still stuck with their 2018 call for AFib screening with ECG. In a JAMA Patient Page, Jill Jin, MD, of Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, explained that within the context of the recommendation, “screening” refers to “performing an… ECG… traditional ECGs are done in doctor’s offices; newer at-home ECG monitors are available but not widely used… or using a device programmed to detect irregular heartbeats (which may or may not be [AFib]),” while usual care refers to “…listening to the heart with a stethoscope… [and]… taking a pulse measurement.”

In a JAMA podcast, task force member Gbenga Ogedegbe, MD, MPH, of New York University in New York City, explained that USPSTF “actually considered the intensity of the screening: Is it a one-time screening strategy, an intermittent screening strategy, or a continuous screening strategy with the use of these devices?”

“Specifically, what the task force found is that the more you screen, the more AFib you can detect,” he noted. “So for one-time screening strategies… they were no more likely than usual care to detect AFib, whereas intermittent and continuous screening strategies, they seemed to identify, in adults [age] ≥50, more effectively than usual care… previously undiagnosed AFib. The reality is, we don’t know the clinical significance of screen-detect AFib and, if anything, the duration of the AFib in these trials [evaluated for the evidence report] is quite small. More importantly, the risk of stroke in… screen-detected AFib is unclear.”

Multiple accompanying editorials offered the “real-world” implications for the updated recommendations.

The relative lack of enthusiasm for AFib screening notwithstanding, “[i]t would be remiss… to ignore the fact that consumer-available technology will permit AFib screening whether clinicians order it or not,” pointed out John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Health Louisville, and Andrew Foy, MD, of Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine in Hershey, in a JAMA Internal Medicine editorial.

“We will increasingly see patients present with the surrogate marker of screen-detected AFib. As with any screening test, the question is whether this knowledge can guide management decisions that ultimately improve outcomes,” they wrote, adding that, based on current data, the answer is “no.”

In a JAMA Cardiology editorial, Rod Passman, MD, MSCE, of Northwestern University in Chicago, and Ben Freedman, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Sydney, stressed that “[r]egardless of how the diagnosis is made, for AFib screening to be fully endorsed, it must first be demonstrated that screen-detected AFib carries the same prognosis and responds similarly to interventions as clinically detected AFib.” They cited data from the GARFIELD-AF study, which “showed similar rates of all-cause mortality, hemorrhagic stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding when treated with anticoagulation,” in those who were asymptomatic at the time of AFib diagnosis. They added that more clarity should come from the ongoing. SAFER and SAFER-AUS trials.

In a JAMA editorial, Philip Greenland, MD, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, asked “[w]hat are the next steps in trying to resolve whether screening for AFib in asymptomatic individuals is justifiable based on well-studied benefits and harms?” He wrote that questions that still need answers include:

- Is there “a threshold for AFib duration that is most strongly associated with stroke risk and therefore most likely to benefit from anticoagulation,”as a short duration of AFib may have [led] to many low-risk patients being diagnosed and treated,” per findings from the 2021 LOOP study.

- Should future trials enroll “only higher risk patients and [identify] those with AFib of longer duration… [a] with many clinical trials, estimated event rates used in study design often do not match the actual results, so very large trial sizes are needed.”

- Can the field of AFib screening meet the challenges put forth by a 2021 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop to back the “great enthusiasm for AFib screening and optimism for the future role of wearables that could revolutionize this field?”

In a JAMA Network Open editorial, Zachary D. Goldberger, MD, and Matthew M. Kalscheur, MD, both of the University of Wisconsin Madison, suggested that other USPSTF guidelines for screening abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and lung cancer, both of which have parameters based on age and smoking history, could help determine the future path of AFib screening.

While they also suggested that “leveraging deep learning algorithms to identify and monitor individuals at higher risk for AFib may be another method to refine the population screened for AFib and, perhaps, increase the yield of monitoring,” Goldberger and Kalscheur stressed that targeted management of patients with AFib through lifestyle interventions was still important.

The current recommendation is based on an evidence report by Leila C. Kahwati, MD, MPH, of RTI International, in Triangle Park, North Carolina, and co-authors. They eventually reviewed 26 studies with >113,000 patients.

Kahwati’s group reported in JAMA that in the STROKESTOP study of twice-daily ECG screening for two weeks, the likelihood of a composite endpoint, which included ischemic stroke, all-cause mortality, and hospitalization for bleeding, was actually lower in the screened group over 6.9 years (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92-1.00, P=0.045). But the study had multiple limitations, such as the fact that the intervention was not masked, and outcome ascertainment was done through national health registry data. Also, about 12% of all the study participants had known AFib, and findings were not reported for “the subgroup of participants without known AFib at baseline.”

Kahwati’s group conceded that other trials showed that “significantly more AFib was detected with intermittent and continuous ECG screening compared with no screening,” with a risk difference range from 1.0% to 4.8%.

And, while treatment with warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants was tied to fewer ischemic strokes and stroke incidence, both carry an increased risk of major bleeding, they noted, stating that “estimates for this harm are imprecise [such as in the SCREEN-AF trial]; no trials assessed benefits and harms of anticoagulation among screen-detected populations.”

As for where the updated USPSTF recommendation falls in the general AFib management spectrum, it will most likely be supported by the American Academy of Family Physicians, which backed the 2018 task force guideline. The American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association are in favor of active screening for AFib in the primary care setting for people >65 years old using pulse assessment followed by ECG.

However, the USPSTF take on AFib screening very different than that of the European Society of Cardiology/European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS), which in 2020, “endorsed opportunistic screening for AFib,” in various groups based on age and stroke risk, by pulse palpation or ECG, Greenland noted. The ESC/EACTS guideline was summarized for the American College of Cardiology by Thomas C. Crawford, MD, of Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor.

Greenland asked “why did the ESC reach a different recommendation than the USPSTF?” He explained that, despite the risks for overdiagnosis or overtreatment, unnecessary anxiety from abnormal findings, and lack of data from trials, “the ESC committee concluded that AFib screening… was justified because of the likely benefit of early detection and treatment in selected older individuals.”

In a 2021 Journal of Clinical Medicine review of the ESC/EACTS guideline, Johanna B. Tonko, MD, of Guy’s the St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in London, and Matthew J, Wright, PhD, MBBS, of King’s College London, pointed out that the European recommendation encourages “the use of new wearable, commercially available single or multiple lead ECG monitors (including photo-plethysmographs on smartphones and smart watches with or without dedicated connectable devices) as AFib screening tools as long as the significance and the treatment implications in case of detecting AFib have been discussed with the patient.”

But they also noted that ESC/EACTS did not offer any “recommendation on the appropriate interval and duration of AFib screening with these devices. Additionally, for the definite diagnosis of AFib the verification of the ECG tracing recording over at least 30 seconds by a physician with expertise in ECG is still required. The latter remains essential to avoid misinterpretation, leading to overdiagnosis, exposure to unnecessary further tests and overtreatment.”

Finally, Goldberg and Kalscheur pointed out that the smartwatch-based Apple Heart study enrolled about 420,000 people so offered hope that “mass enrollment in a clinical AFib screening trial is feasible.”

Disclosure:

The USPSTF is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The evidence report was funded by AHRQ.USPSTF members reported travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in USPSTF meetings.

Greenland reported support from the NIH and the American Heart Association.

Mandrola, Foy Goldberger, and Kalscheur reported no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Passman reported relationships with Janssen and Medtronic. Freedman reported support from, and/or relationships with, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, OMRON, and Alivecor.

Jin reported serving as JAMA associate editor.

Kahwati reported no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. A co-author reported support from a National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health National Research Service Award Institutional Research Training Program at the University of North Carolina.

by

Shalmali Pal, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

Kaiser Health News

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.