Most people in the U.S. should get going on colorectal cancer (CRC) screening at age 45, while those ages ≥76 have the option to wind down routine CRC screening, according to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

In an updated recommendation, the task force gave a “B” grade to CRC screening in asymptomatic people ages 45 to 49, a “C” grade for selective CRC screening in those ages 76 to 85, and an “A” grade for screening in all adults ages 50 to 75.

In terms of CRC screening in an older population, “[e]vidence indicates that the net benefit of screening all persons in this age group is small. In determining whether this service is appropriate in individual cases, patients and clinicians should consider the patient’s overall health, prior screening history, and preferences,” advised Karina W. Davidson, PhD, MASc, of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in New York City, and co-authors.

As for the new call for screening in the younger age group, the “USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening…has moderate net benefit,” although CRC incidence is climbing in younger people, they wrote in JAMA.

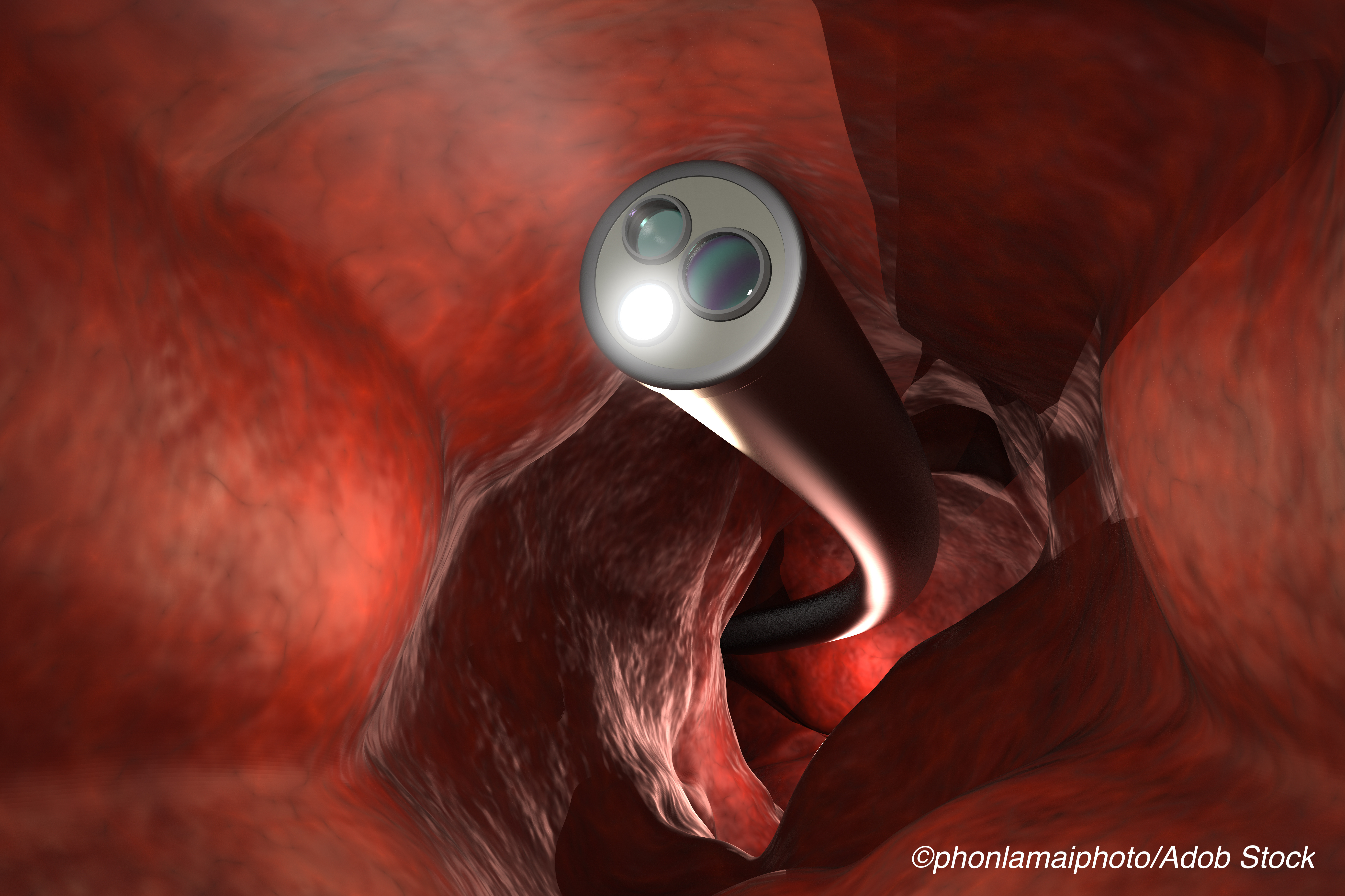

In a JAMA Patient Page, Jill Jin, MD, MPH, of Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, summarized the types of CRC screening tests currently available: colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, CT colonography (CTC), fecal occult blood test (FOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and stool DNA test.

“There are pros and cons to each of these tests, and there are different screening intervals recommended for each. The USPSTF does not specifically recommend using one test versus another,” she noted. The CDC stresses that “[t]here is no single ’best test’ for any person,” and the most suitable test depends on patient and physician preference, medical conditions, likelihood of undergoing any CRC screening test, and available resources for testing and follow-up.

Several accompanying editorials offered praise for the updated guideline, while also highlighting opportunities to do better in raising awareness of, and adherence with, CRC screening.

In JAMA, Kimmie Ng, MD, MPH, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and co-authors, explained that in 2018, the American Cancer Society called for lowering the recommended age for CRC screening from age 50 to 45 because of a rising incidence of young-onset CRC.

They stressed that the younger age for CRC screening in the updated USPSTF guideline has “moved the field one step forward,” but that more could be done on a societal level to encourage CRC screening, such as employers providing paid “wellness days” to undergo testing, bundling FIT screening with flu shots, or safe-ride services post-sedation, particularly for patients who lack transportation.

While the task force stopped short of declaring one CRC screening test a “winner,” they emphasized the importance of “providing patients with various approaches toward screening to improve compliance with some form of screening,” noted David B. Stewart, MD, of the University of Arizona-Banner University Medical Center in Tucson, in JAMA Surgery.

He pointed out that CRC screening “is not synonymous with endoscopy… multiple trials demonstrate a reduction in CRC deaths with other approaches” and challenged the research community to improve non-invasive screening mechanisms with an eye to boosting screening compliance.

On the dollars and cents front, “the USPSTF guidelines directly inform insurance coverage and waiving of cost sharing as part of federal law,” noted Shivan J. Mehta, MD, MBA, MSHP, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and co-authors in JAMA Network Open. Currently, Medicare covers screening colonoscopies once every 24 months for people at high risk for CRC, and once every 120 months, or 48 months after a previous flexible sigmoidoscopy, for those at average risk. Medicare does not have a minimum age requirement for screening.

But having the test paid for may not be enough to get communities who are most often hard-hit by CRC incidence to make screening appointments, they wrote. “Implementation of the revised recommendations…could reduce access among individuals who are medically underserved if capacity is not expanded, or it may simply result in improved outcomes among individuals with more advantages that are not shared by others, thus widening an existing gap,” they cautioned.

All of the editorialists stressed that more needed to be done in address racial and socioeconomic disparities across CRC screening-eligible populations, such as low incidence of testing among Latinx and Black populations, barriers to access among those with mental health issues, and financial hardships faced by those who are uninsured or underinsured.

“As policy makers, health care systems, and clinicians respond by designing strategies that expand screening, we urge the thoughtful incorporation of practices to ensure equity in access and facilitate learning from implementation challenges and successes across populations. This is an opportunity to reduce the burden of CRC starting at age 45 years, but it is also a reminder to ensure the benefits are realized equitably,” Mehta’s group wrote.

The updated guideline is based on an evidence report and a modeling study.

For the evidence report, Jennifer S. Lin, MD, MCR, of Kaiser at Permanente Northwest in Portland, Oregon, and co-authors, evaluated 33 studies on the effectiveness of screening, 59 on performance of screening tests, and 131 on the harms of screening.

They found the following versus no screening:

- In four randomized clinical trials, intention to screen with one- or two-time flexible sigmoidoscopy was tied to a decrease in CRC-specific mortality (incidence rate ratio 0.74, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.80).

- In five trials, annual or biennial guaiac FOBT was tied to a reduction of CRC-specific mortality after 2 to 9 rounds of screening for a relative risk at 19.5 years of 0.91 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.98), and an RR at 30 years of 0.78 [95% CI 0.65 to0.93).

- In three observational studies, screening colonoscopy or FIT was associated with lower risk of CRC incidence or mortality.

In addition, Lin’s group reported that the pooled sensitivity to detect adenomas ≥6 mm was similar between CT colonography with bowel prep and colonoscopy. But in studies of pooled values, commonly evaluated FIT and stool DNA with FIT performed better than high-sensitivity guaiac FOBT for cancer detection.

As for possible harms, perforations and major bleeding were risks with screening colonoscopy, while ionizing radiation could be an issue with CTC, as could extracolonic findings. “It is unclear if detection of extracolonic findings on CT colonography is a net benefit or harm,” the authors noted.

A review limitation was the exclusion of people with gastrointestinal symptoms and those with a hereditary risk for CRC.

In the modeling study, Amy B. Knudsen, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and co-authors used three microsimulation models of CRC screening—SimCRC, CRC-SPIN, and MISCAN—in a hypothetical cohort of people in the U.S., ages 40, at average CRC risk.

They assessed for estimated life-years gained (LYG) relative to no screening, lifetime number of colonoscopies, number of complications from screening, and balance of incremental burden and benefit. “Efficient strategies were those estimated to require fewer additional colonoscopies per additional LYG relative to other strategies,” the authors explained.

Knudsen’s group reported that estimated LYG from screening strategies ranged from 171 to 381 per 1,000/people age 40, and that lifetime colonoscopy burden ranged from 624 to 6,817/per 1,000 individuals, while screening complications ranged from five to 22/1,000 individuals.

They found that 41 of 49 strategies specified screening beginning at age 45, and that the additional LYG from continuing screening after age 75 were generally small.

Based on the 2016 USPSTF CRC screening recommendation, “lowering the age to begin screening from 50 to 45 years was estimated to result in 22 to 27 additional LYG, 161 to 784 additional colonoscopies, and 0.1 to 2 additional complications per 1000 persons. Assuming full adherence, screening outcomes and efficient strategies were similar by sex and race and across 3 scenarios for population risk of colorectal cancer,” Knudsen and co-authors wrote.

They also pointed that “the findings from this analysis are consistent with those of the 2016 evidence report,” when there was “limited evidence” to support CRC screening in younger people. While current data “remains sparse,” according to Knudsen’s group, “there is clearer evidence that colorectal cancer incidence in the US is increasing before age 50” so starting CRC screening at 45 “provides an efficient balance of colonoscopy burden and life-years gained.”

The updated guideline continues to track with CRC screening recommendations from others, such as the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force, with the latter group suggesting screening at age 45 for Black adults and screening at 40 for people with a CRC family history. Davidson and co-authors pointed out that “specific recommended tests and frequency of screening may vary” between all the guidelines.

-

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) in asymptomatic adults ages 45 to 49; all adults age 50 to 75; and some adults ages ≥76.

-

The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that CRC screening starting at age 45 has moderate net benefit, as CRC incidence is on the rise in younger people.

Shalmali Pal, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

The USPSTF is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The evidence report and modeling study were funded by AHRQ.

USPSTF members reported travel reimbursement and an honorarium for participating in USPSTF meetings.

Ng reported support from, and/or relationships with, Pharmavite, Evergrande Group, Janssen, Revolution Medicines, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Seattle Genetics, Array Biopharma, BiomX, and X-Biotix Therapeutics. A co-author reported relationships with JAMA, Pfizer, and GRAIL.

Lin and co-authors, as well as Stewart, reported no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Knudsen and some co-authors reported support from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Jin reported serving as JAMA associate editor.

Metha reported support from the NCI. A co-author reported serving as JAMA Network Open associate editor.

Cat ID: 23

Topic ID: 78,23,730,16,23,192,925

Create Post

Twitter/X Preview

Logout