Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) substantially reduced subsequent suicide risk among hospitalized patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) compared to non-ECT treatment, with the greatest benefit manifesting in older patients and those with psychotic depression, researchers found.

According to guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association, ECT is an effective treatment option indicated for patients with severe major depression, “including those with psychosis, catatonia, and/or an elevated suicide risk,” Axel Nordenskjöld, MD, PhD, Ida Rönnqvist, MD, and Fredrik K. Nilsson, MD, of Örebro University in Örebro, Sweden, explained in JAMA Network Open. However, ECT’s benefit is often questioned, partially due to a lack of data regarding its effects on suicide risk—a pressing concern, given that patients with depression face an increased suicide risk for years following discharge from psychiatric inpatient care, particularly in the first 3 months post-discharge.

And the data that does exist offers conflicting conclusions—one recent register-based study from Denmark found that ECT was linked with increased risk of suicide, while other smaller studies found that ECT was associated with both an increased and decreased suicide risk, differences that Nordenskjöld and colleagues chalked up to incomplete adjustment for confounding factors.

For their analysis, Nordenskjöld and colleagues used more detailed population registers than previous research in order to assess the association between ECT indicated for depression and subsequent risk of suicide.

They found that, compared with non-ECT, use of ECT for patients with MDD was associated with a 28% reduction in suicide risk within 12 months of discharge and a 42% reduction in the first 3 months. Patients with psychotic depression and patients ages 45-64 years or 65 years and older saw an even greater risk reduction (80%, 46%, and 70%, respectively). Moreover, ECT was associated with reduced all-cause mortality within 3 and 12 months of inpatient care compared with non-ECT, they added.

“The results of this cohort study support the continued use of ECT to reduce suicide risk among hospitalized patients who are severely depressed, especially older patients and those with psychotic features,” they concluded.

In an invited commentary accompanying the study, Bradley N. Gaynes, MD, MPH, of the Gillings Global School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina, argued that this research by Nordenskjöld et al “provided the strongest evidence yet that the use of ECT, when applied to the proper group, is associated with a reduced risk of suicide. This is important information that patients, families, health care professionals, and payors can consider in deciding whether ECT is indicated for an individual with at least a moderate severity of MDD, with or without psychotic symptoms.”

However, he added, the study was not without limitations.

“One of the key challenges in any cohort study that uses large databases is to account for cointerventions that might differ between the 2 groups, such as number of contacts and other clinical management activities that might occur during the follow-up phase, because that information may not be collected,” he wrote. The study authors acknowledged this particular limitation, noting that these unmeasured factors could potentially explain the differences between treatment groups.

For their study, Nordenskjöld and colleagues pulled data from Swedish national registries for patients with a record of inpatient care for moderate depression, severe depression, or severe depression with psychosis from Jan. 1, 2021, through Oct. 31, 2018. Patients with mild or unspecified depression, manic episodes, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizotypal disorders, or delusional disorders, and those under 18 years of age were excluded.

The primary study outcome was suicide within 3 and 12 months of admission to inpatient care; the study authors also included risk factors for suicide as covariates, including older age, male sex, a greater severity of depression, family history of mental disorder, previous suicide attempts or self-harming behavior, psychiatric comorbidities, somatic comorbidities, unemployment, living alone, and a family history of suicide. They also included use of lithium and antidepressants in the 100 days prior to the inpatient episode.

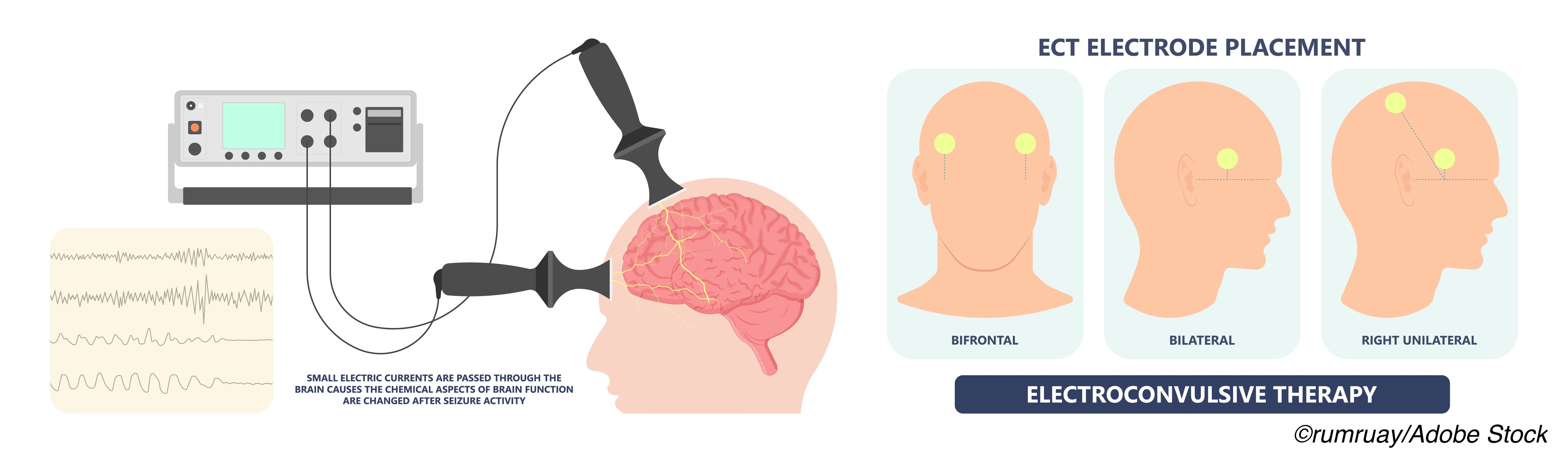

For patients with MDD who received ECT during their inpatient visit, therapy was typically administered three times a week using the bidirectional constant-current brief-pulse Mecta (Mecta Corp) or Thymatron (Somatics Inc) device.

The study included 28,557 patients (mean [SD] age, ECT group, 55.9 [18.4] years; non-ECT group, 45.2 [19.2] years; 12,701 men [44.5%] and 15,856 women [55.5%]). The total number of inpatient episodes was 43,169, of which 11,578 (26.8%) involved ECT. Of the study population, 5,525 patients with a first episode of inpatient care during the study period in each group was successfully matched.

In the matched sample, “ECT was associated with a significantly decreased risk of suicide within 12 months compared with non-ECT (hazard ratio [HR], 0.72; 95% CI, 0.52-0.99),” they wrote. “A total of 62 of 5,525 patients (1.1%) in the ECT group and 90 of 5,525 patients (1.6%) in the non-ECT group died of suicide within 12 months. In the episode-based analysis at 12 months, suicide risk did not significantly differ between the ECT and non-ECT groups in the main analysis (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.65-1.03) or after adjustment for treatment with lithium and/or antidepressants during follow-up (HR, 0.93; 95% CI,0.73-1.17).”

At 3 months, “ECT was associated with a significantly lower risk of suicide than non-ECT (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.40-0.83), and this association was retained in sensitivity analyses adjusting for treatment with lithium and/or antidepressants during follow-up (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.42-0.86),” they added.

Electroconvulsive therapy was also associated with lower suicide risk compared to non-ECT among patients ages 45-64 years (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.30-0.99) and 65 years or older (HR, 0.30; 95% CI,0.15-0.59), but not in patients ages 18 to 44 years (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.68-2.16). Also, there was a significant association between reduced suicide risk and ECT in patients with severe depression and psychosis (HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.08-0.54; P=0.001), but not of patients with moderate depression (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.46-1.87) or severe depression without psychosis (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.41-1.04).

Beyond those cited by Gaynes, study limitations included potential selection bias since patients who received ECT were more likely to have severe depression and psychotic features than non-ECT patients, and, since depression with suicide risk is an indication for ECT, the risk of suicide judged by the treating psychiatrist was likely higher in the ECT group.

-

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) substantially reduced subsequent suicide risk among hospitalized patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) compared to non-ECT treatment, with the greatest benefit manifesting in older patients and those with psychotic depression.

-

Note that the study authors were not able to account for cointerventions beyond ECT that may have differed between the two treatment groups, which may account for the differences in suicide risk observed in this analysis.

John McKenna, Associate Editor, BreakingMED™

Nordenskjöld reported receiving personal fees from Lundbeck outside the submitted work.

Gaynes had no relevant relationships to disclose.

Cat ID: 55

Topic ID: 87,55,730,192,55,921

Create Post

Twitter/X Preview

Logout